[History of Science - Scientific Revolution - 17th century] [Astronomy - Comets]

GALILEO GALILEI

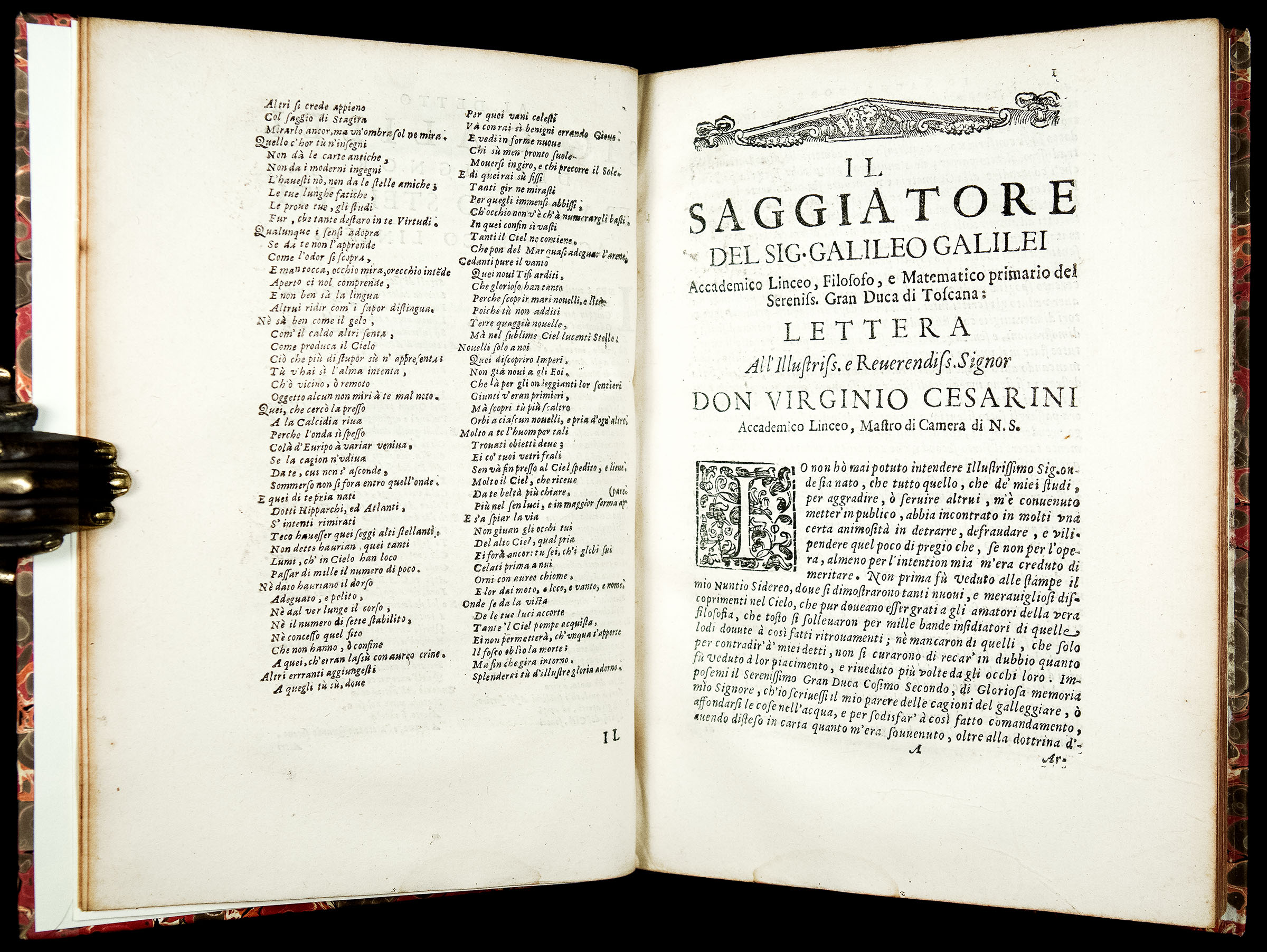

IL SAGGIATORE

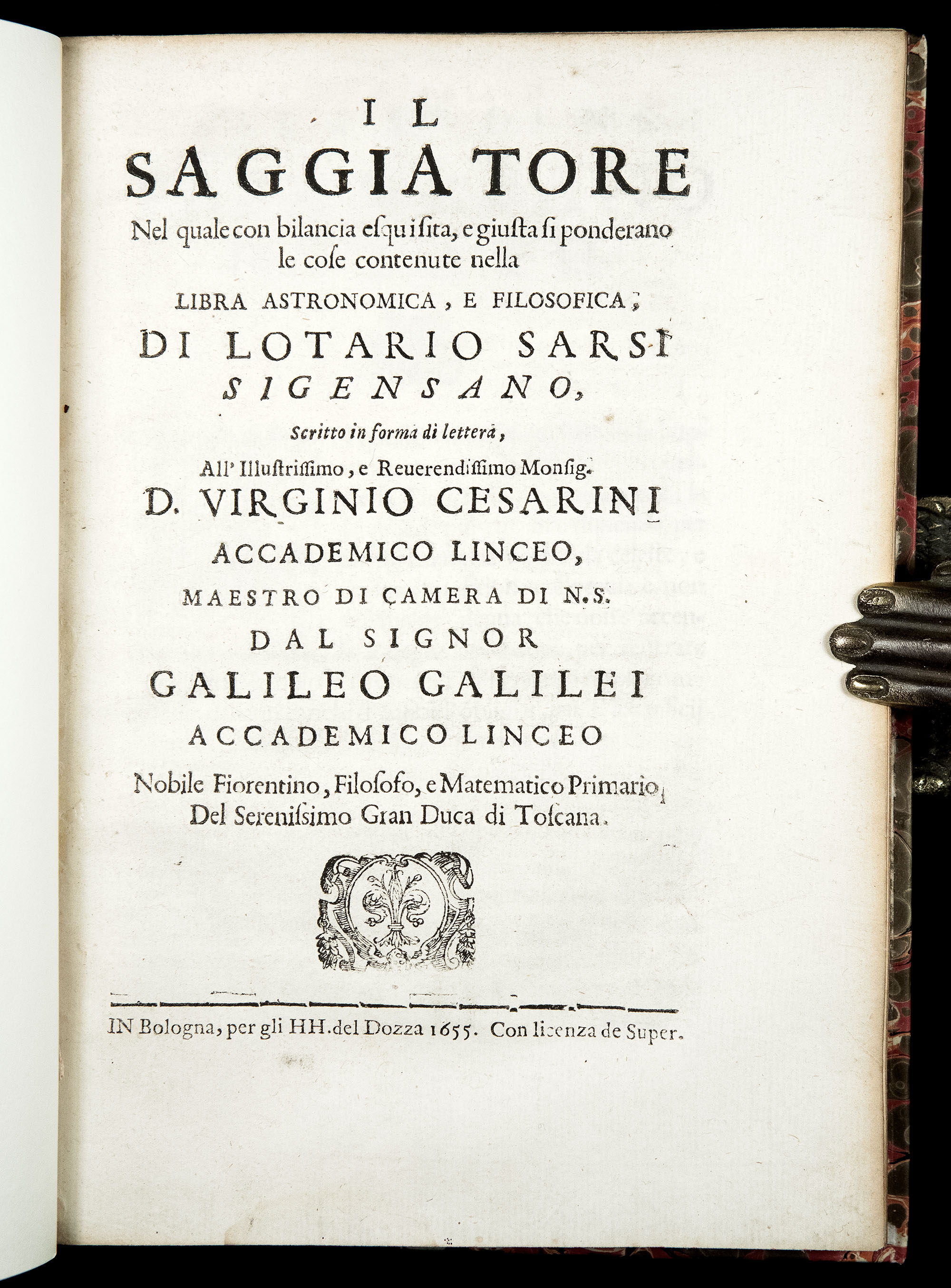

nel quale con bilancia esquisita e giusta si ponderano le cose

contenute

nella 'Libra astronomica e filosofica' di Lotario Sarsi […]

scritto in forma di lettera [...]

$1,800

Printed in Bologna by heirs of Evangelista Dozza, 1655.

Text in Italian. Illustrated with woodcuts.

2ND EDITION of “ONE OF THE MOST CELEBRATED POLEMICS IN SCIENCE” (DSB V, 243), and ONE OF THE PIONEERING WORKS OF THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD, emphasizing the importance of mathematical approach to scientific inquiry.

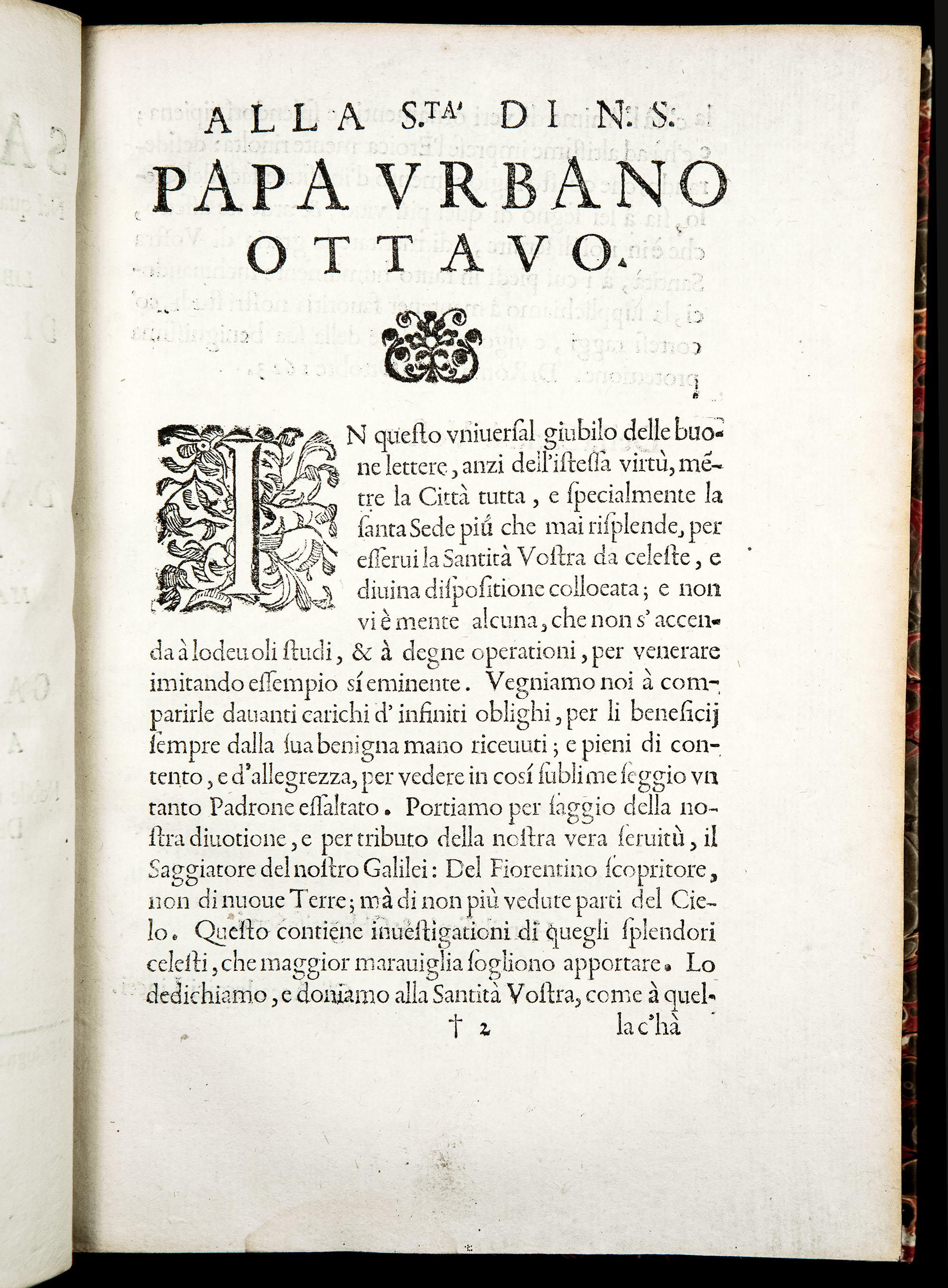

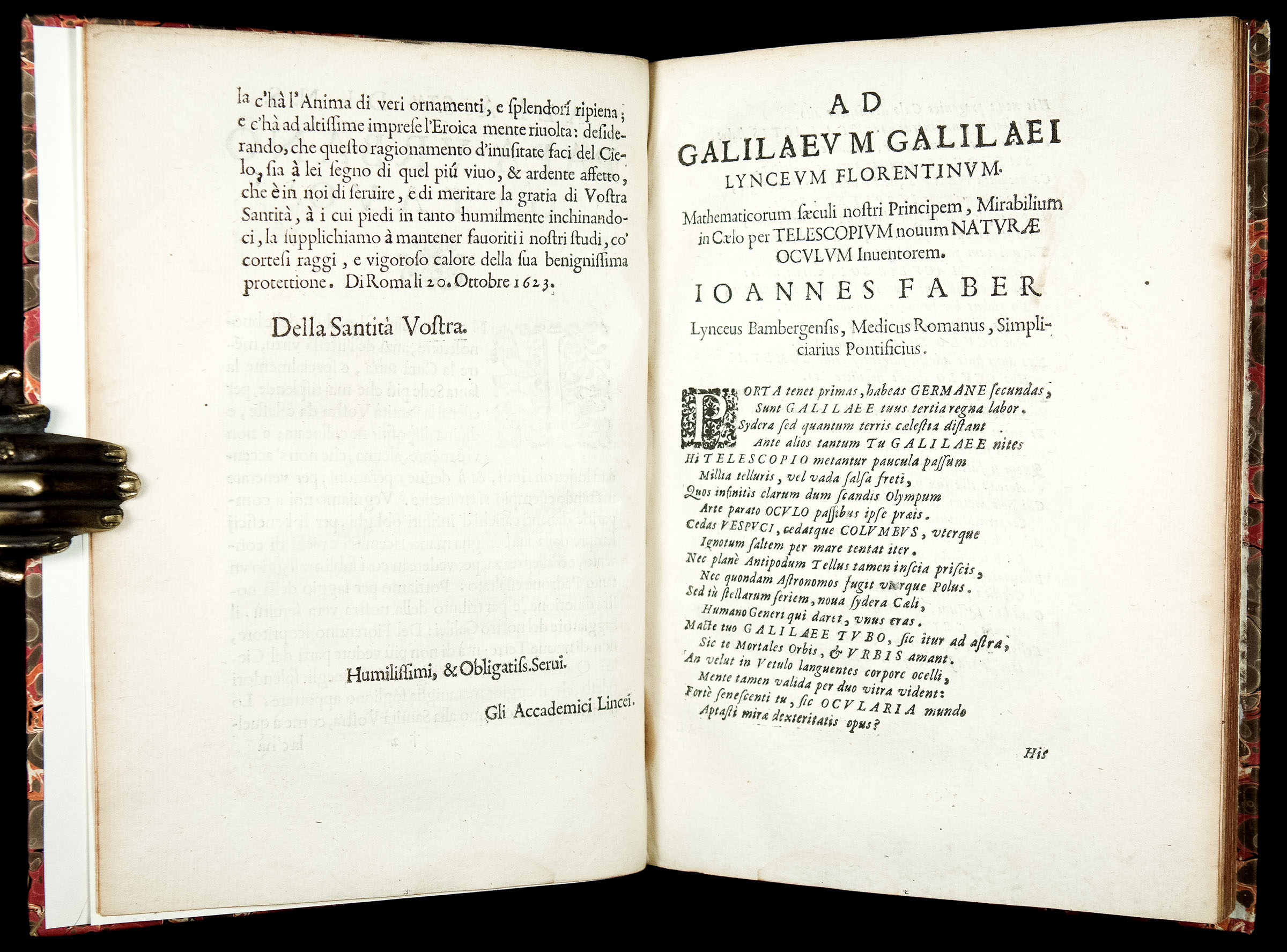

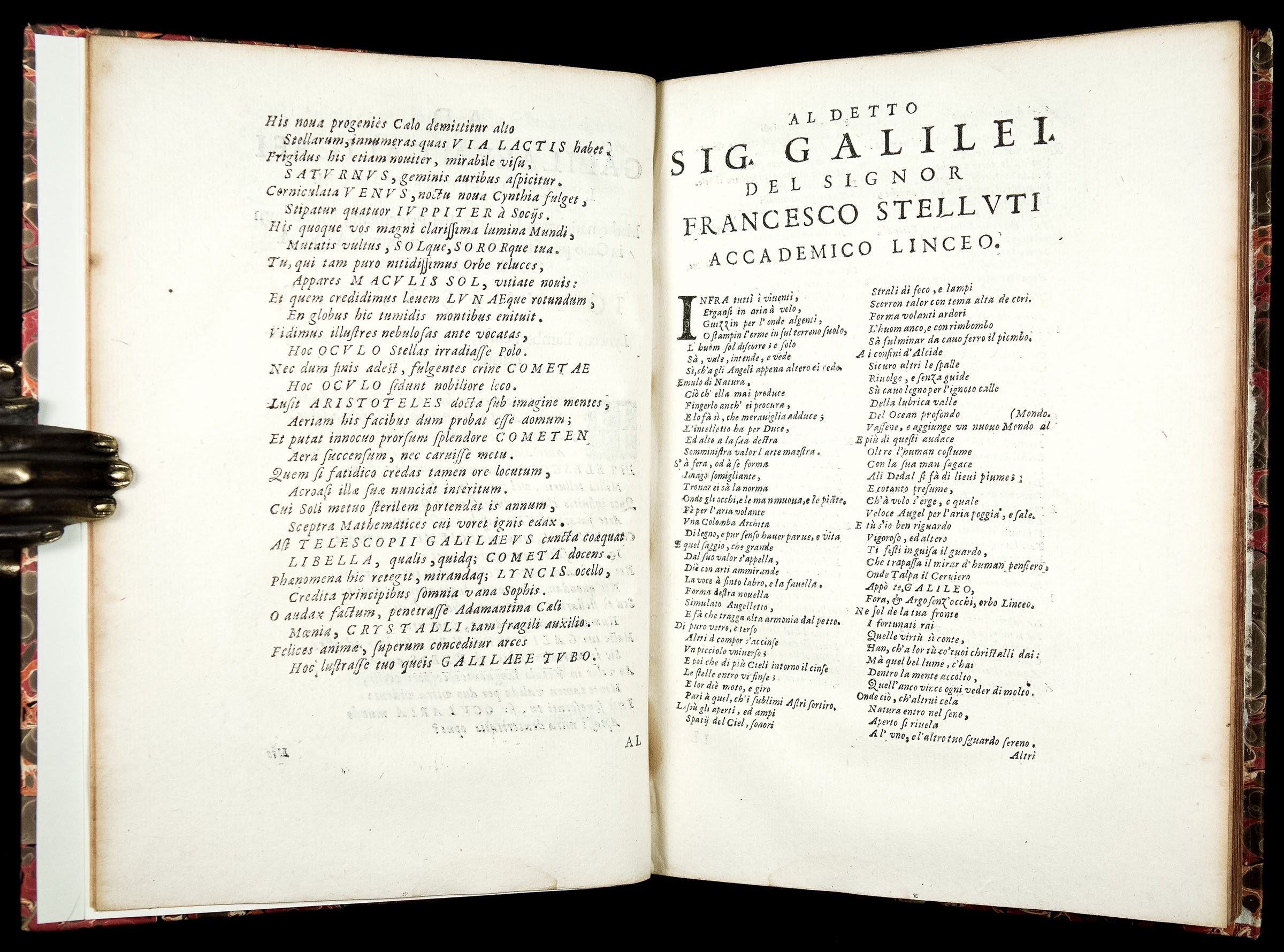

First printed in Rome in 1623, Il Saggiatore was dedicated to the new Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini), Galileo's friend and a patron of science and the arts.This 1655 edition also includes Galileo’s original dedication to Pope Urban VIII (dated Oct. 20, 1623), as well as two prefatory poems eulogizing Galileo and his invention of telescope etc. written by his friends: one by Francesco Stelluti (1577-1652), an Italian polymath scholar, a co-founder of the Accademia dei Lincei; the other by Giovanni (or Johann) Faber (1574–1629), a German papal doctor and botanist, originally from Bamberg, who lived in Rome from 1598 and was curator of the Vatican botanical garden, and the secretary of the Accademia dei Lincei.

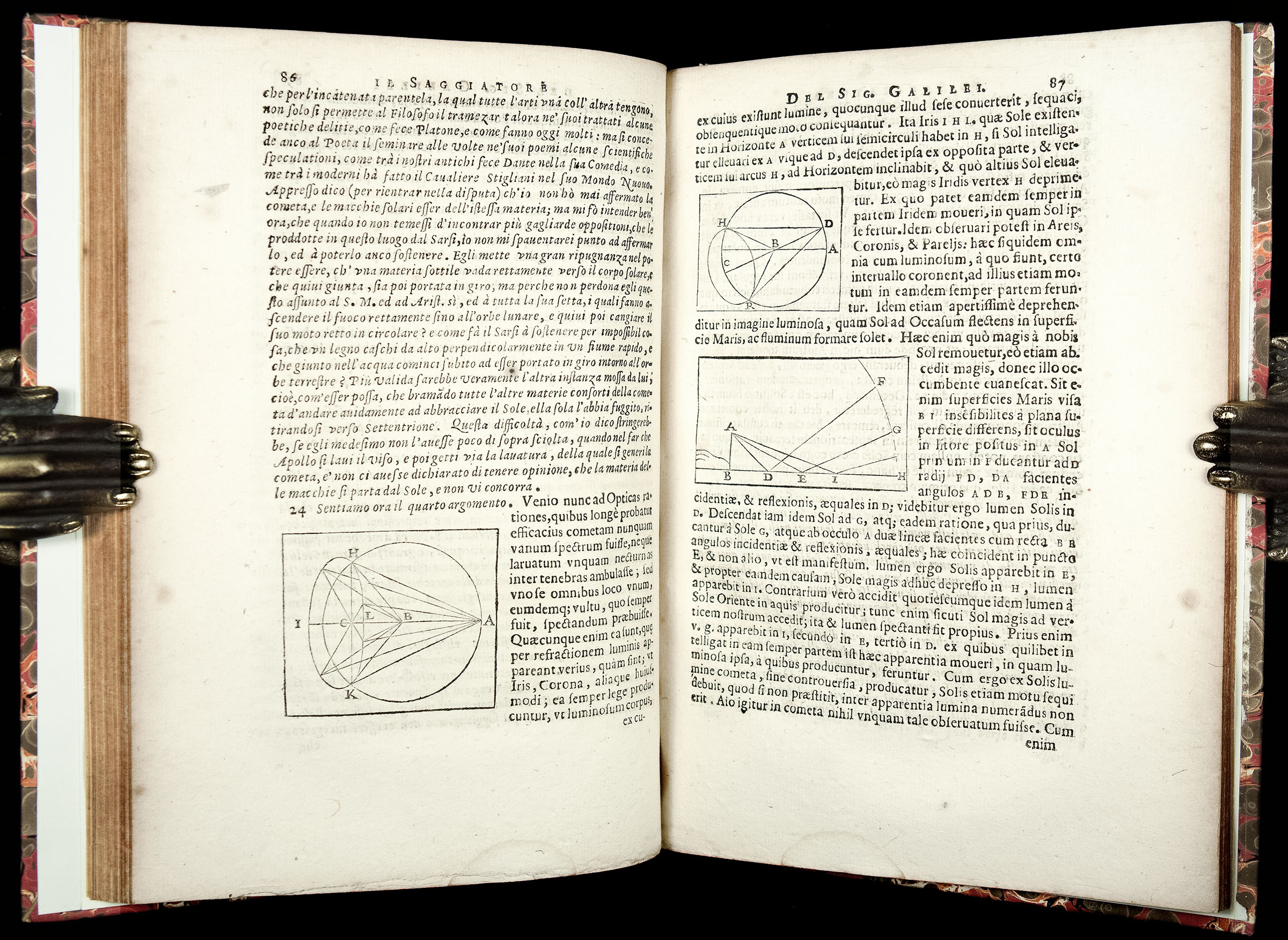

Often viewed as Galileo’s "scientific manifesto," Il Saggiatore (i.e. “The Assayer”) was the first of Galileo’s works written after the Inquisition’s warning not to propound or defend the Copernican theory (which he still does, although in a covert way). The writing of Il Saggiatore was precipitated by the appearance of three comets in the autumn of 1618 and the dispute over whether they were atmospheric or celestial phenomena. The work is believed to have significantly aggravated (or, perhaps, even originated) the rift between Galileo and the Jesuits, which ultimately led to his imprisoned by the Inquisition after the publication of the Dialogo in 1632.

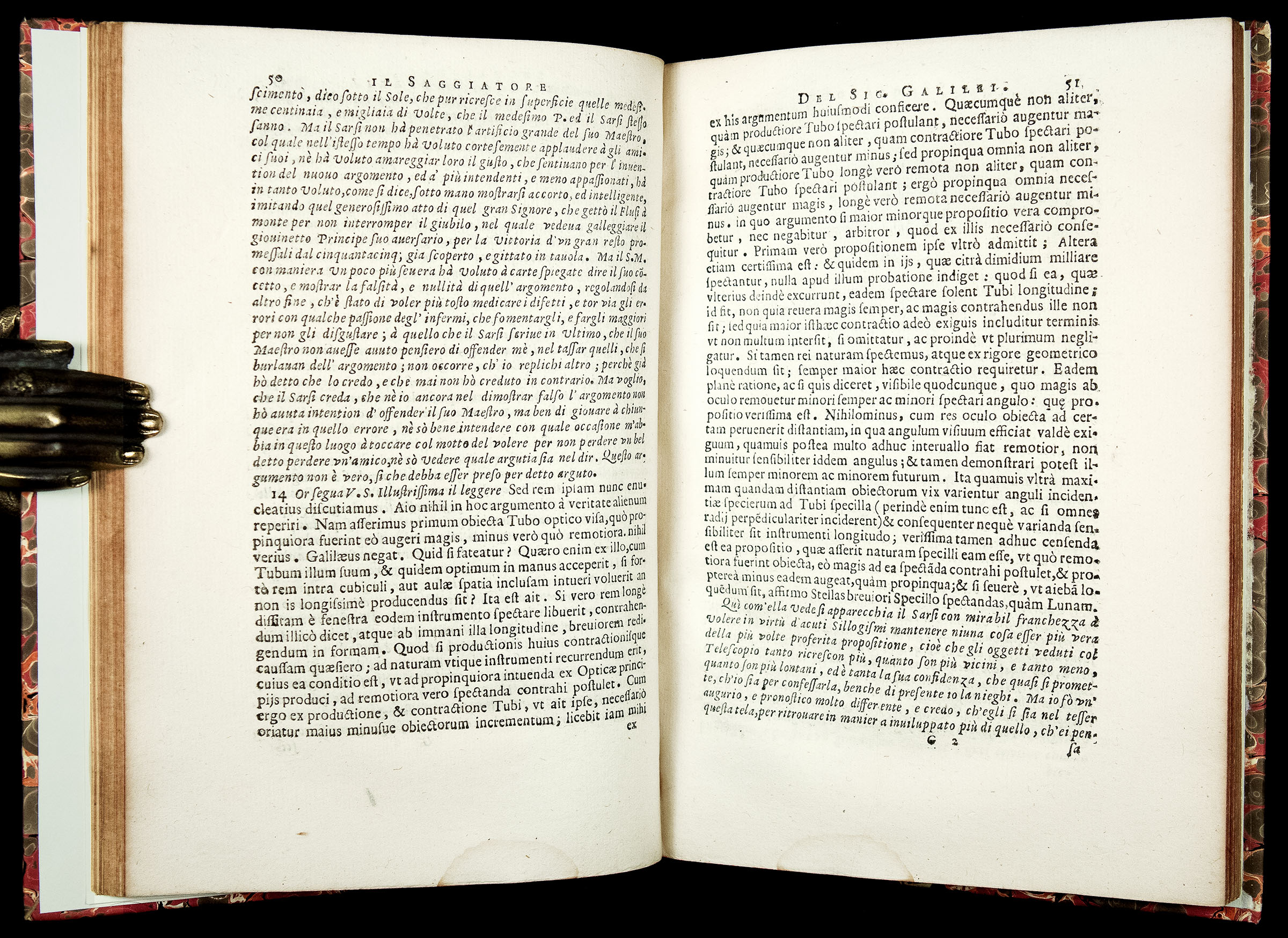

Galileo's masterful polemic - Il Saggiatore - was written in response to Orazio Grassi, mathematician at the Jesuit Collegio Romano, who in 1619 had published, under the pseudonym Lotario Sarsi, an attack on Galileo after the latter had criticized his views on comets. Unable to defend the Copernican doctrine (which was declared heretical in 1616), Galileo in his response, addressed to a young admirer named Virginio Cesarini, avoided all discussion of the planetary movement, concentrating instead on a general discussion of the proper scientific approach to the investigation of celestial phenomena.

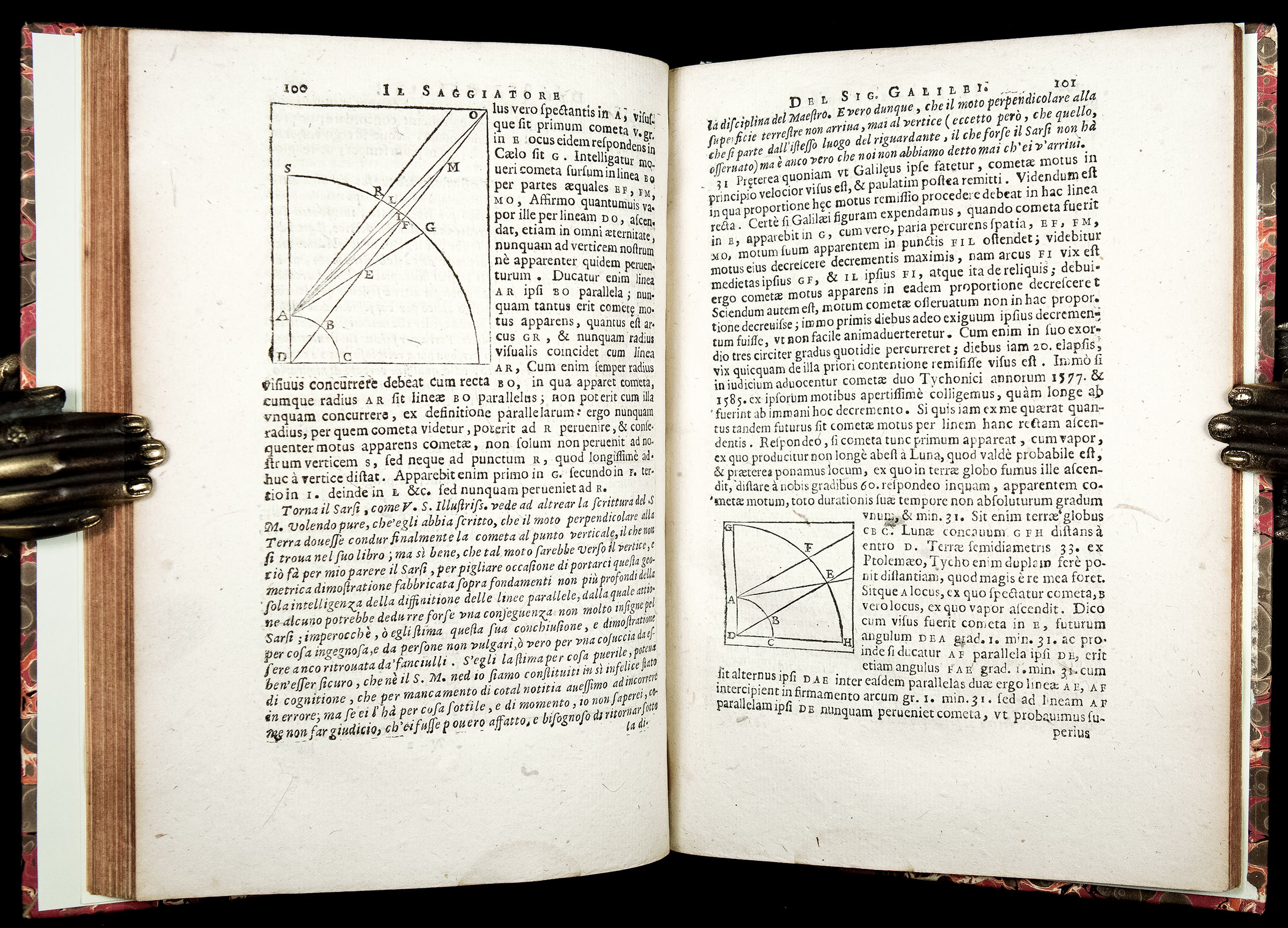

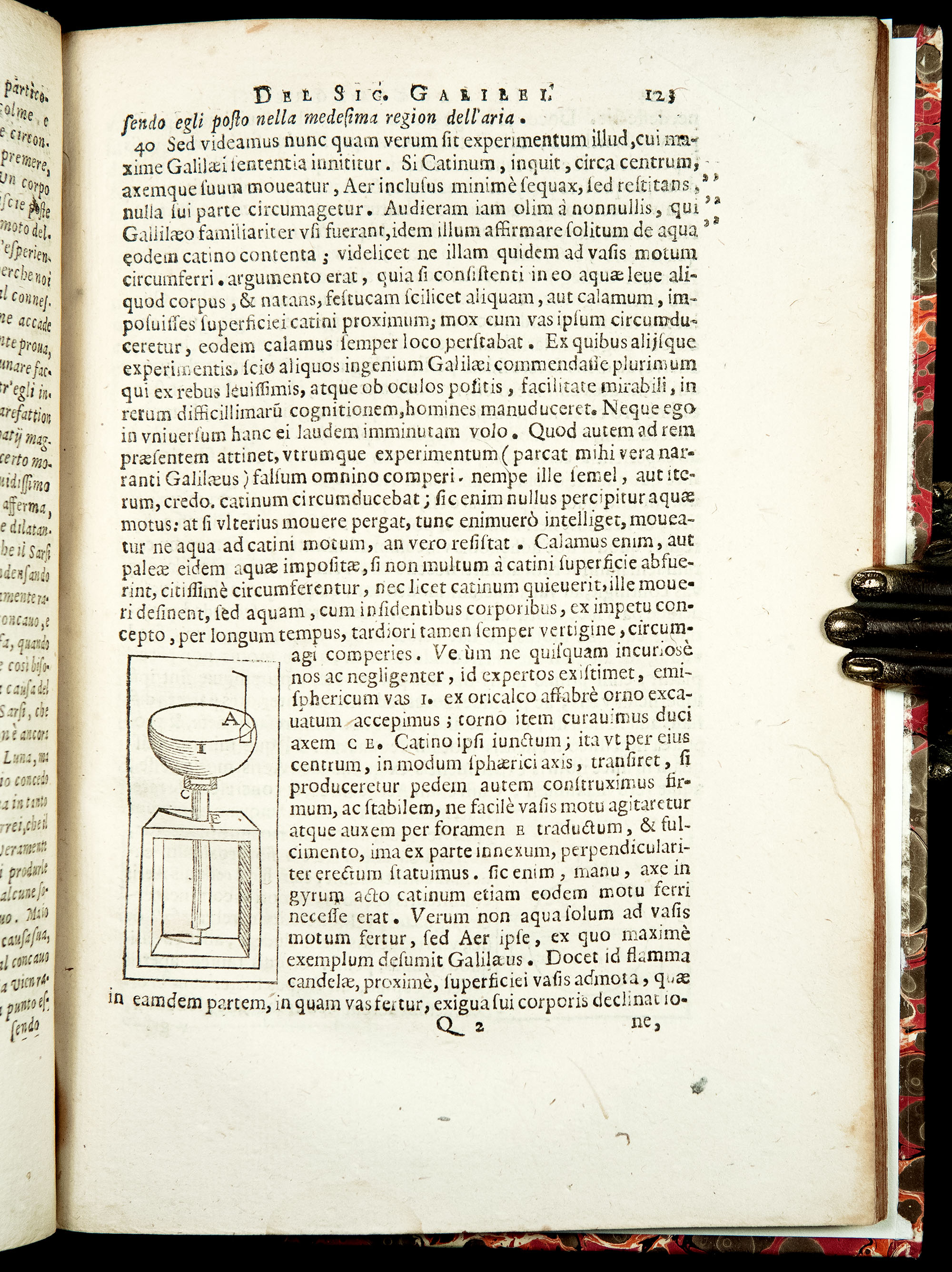

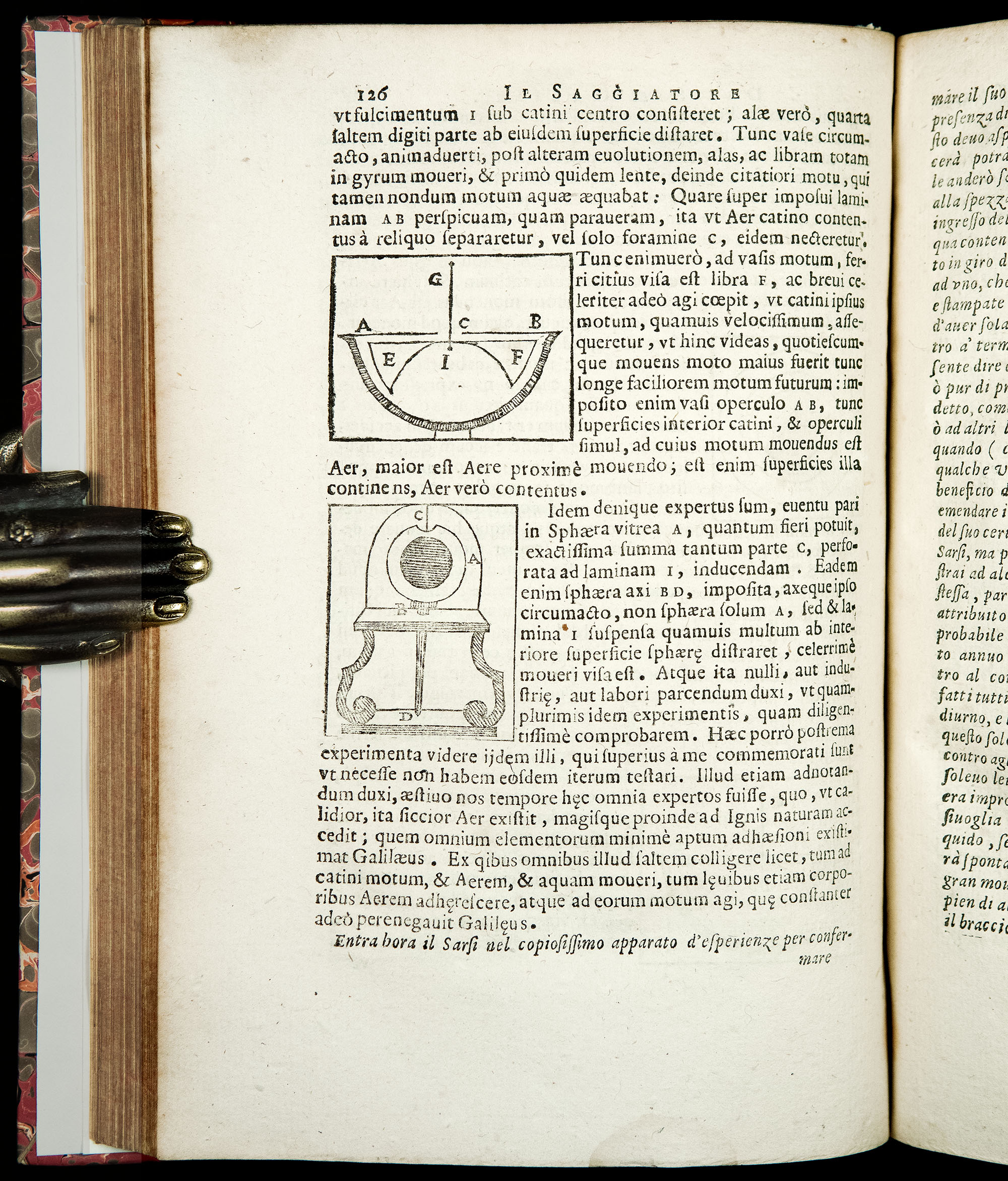

The Galileo’s argument was that no theory of comets could be advanced unless it could be proven that they were concrete moving objects rather than mere optical effects of solar light, a proof that he considered impossible. In advancing this thesis he set forth some fundamental axioms of the modern scientific method: he "distinguished physical properties of objects from their sensory effects, repudiated authority in any matter that was subject to direct investigation, and remarked that the book of nature, being written in mathematical characters, could be deciphered only by those who knew mathematics" (DSB).

Galileo brilliantly criticized Grassi's method of inquiry, heavily influenced by his religious belief, and insisted that natural philosophy (i.e. physics) should be mathematical. This is the book containing Galileo’s famous statement that mathematics is the language of science. Only through mathematics can one achieve lasting truth in physics. Those who neglect mathematics wander endlessly in a dark labyrinth.

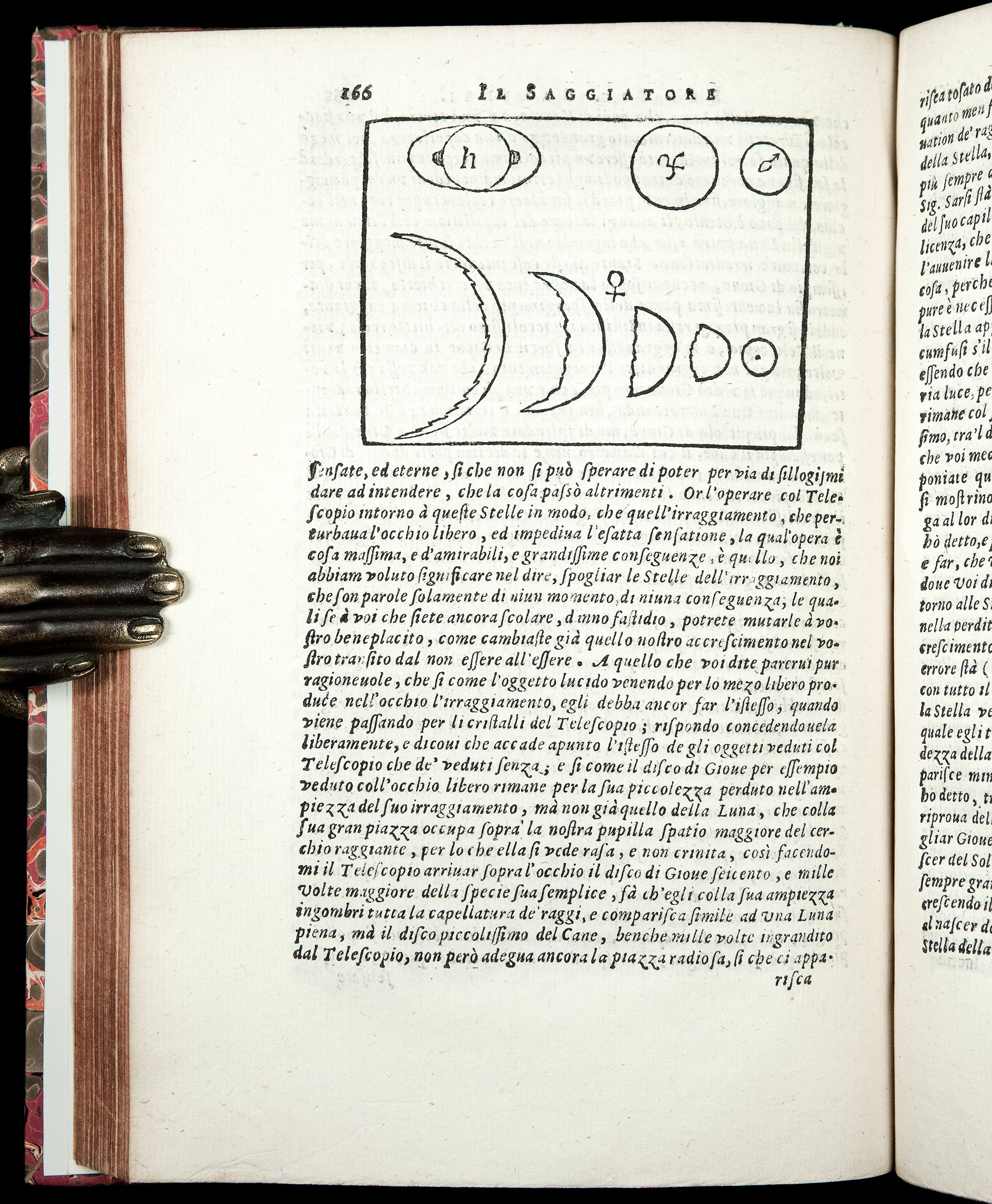

Galileo used a sarcastic and witty tone throughout the essay. The book was read with delight at the dinner table by Urban VIII "This was a truly masterful piece of sarcastic invective and criticism. It is still read today in Italian language classes in Italy as a fine example of the use of rhetoric devices in the Italian language.” (P. Machamer, The Cambridge Companion to Galileo, 1998, p. 21). The woodcut on p. 166 of this 1655 edition closely reproduces the copperplate engraving in the 1623 First Edition, which contained THE EARLIEST PRINTED ILLUSTRATION OF THE RING OF SATURN, along with the planet Mars in inferior and superior conjunction, and the phases of Venus.

Galileo Galilei (1564 - 1642) was an Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer and philosopher who played a key role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations, and a strong support of Copernicanism. His contributions to observational astronomy include the telescopic confirmation of the phases of Venus, the discovery of the four largest satellites of Jupiter (named the Galilean moons in his honour), and the observation and analysis of sunspots.

"Galileo, perhaps more than any other single person, was responsible for the birth of modern science.” (Stephen Hawking)

Bibliographic references:

Cinti 132; Riccardi I, 518; Houzeau-Lancaster I, 3386.

Physical description:

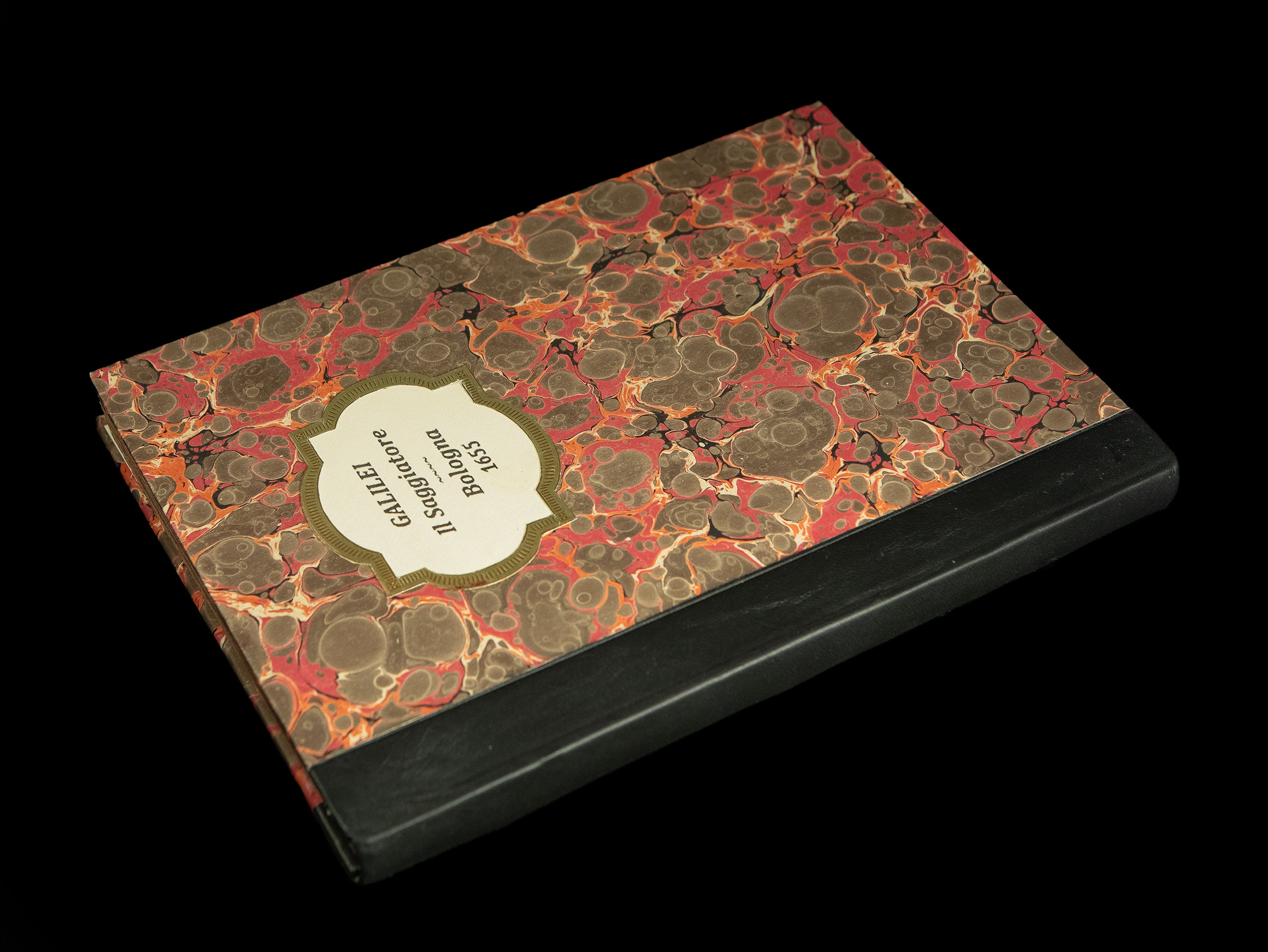

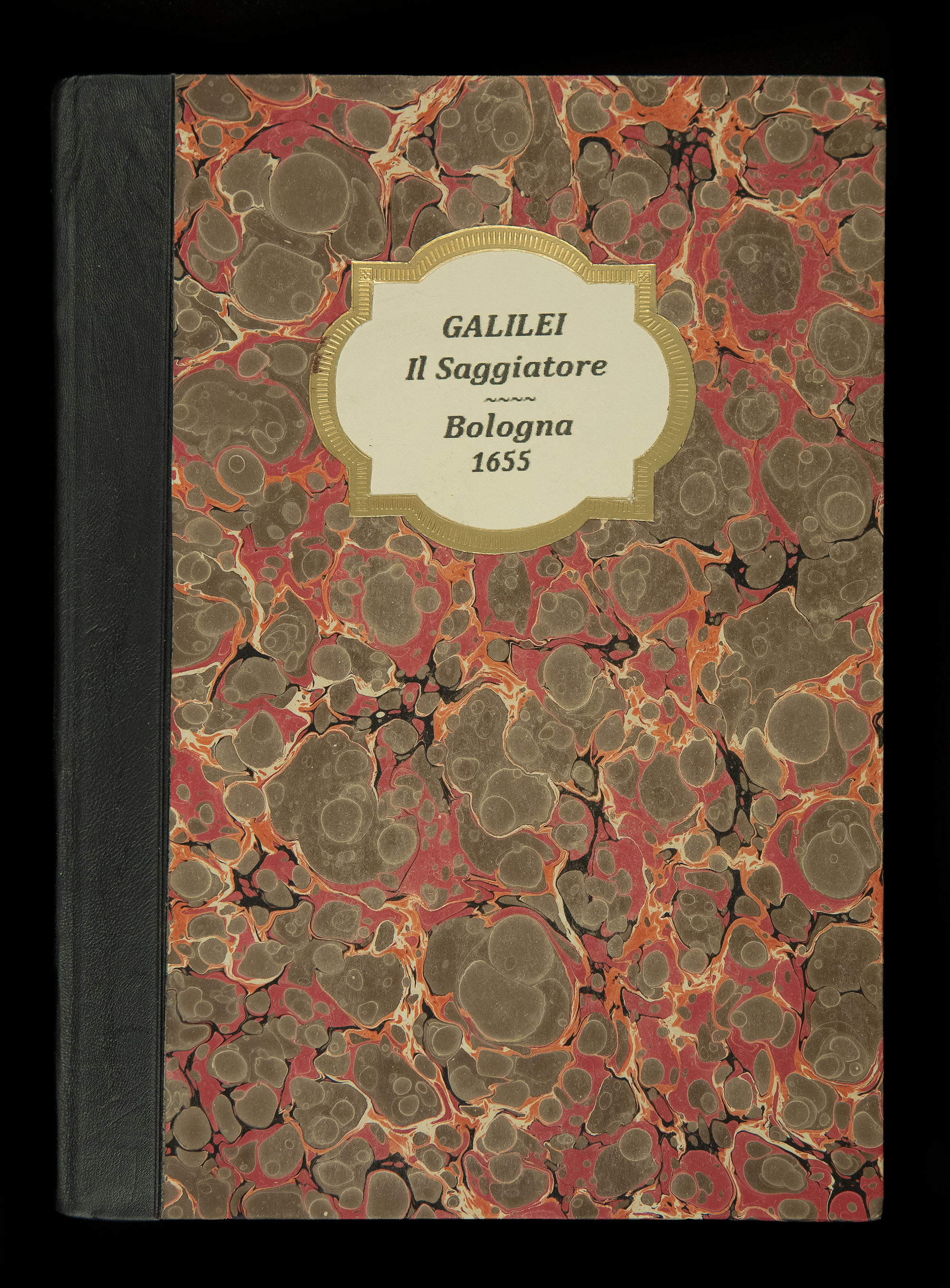

Quarto; text block measures 23 cm x 16.5 cm, wide margins. All edges gilt. Rebound in modern quarter black leather over marbled boards; unlettered flat spine; printed paper label in gilt frame to front cover. Edges rouged.

Pagination: [8], 179, [1] pp.

COMPLETE.

Title-page with a woodcut vignette. Woodcut illustrations and diagrams in text, as well as several woodcut decorative head-pieces and initials. Text printed in roman and italic type.

Preliminaries include Galileo’s dedication to Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini), and laudatory poems on Galileo by his friends Francesco Stelluti and Johann Faber.

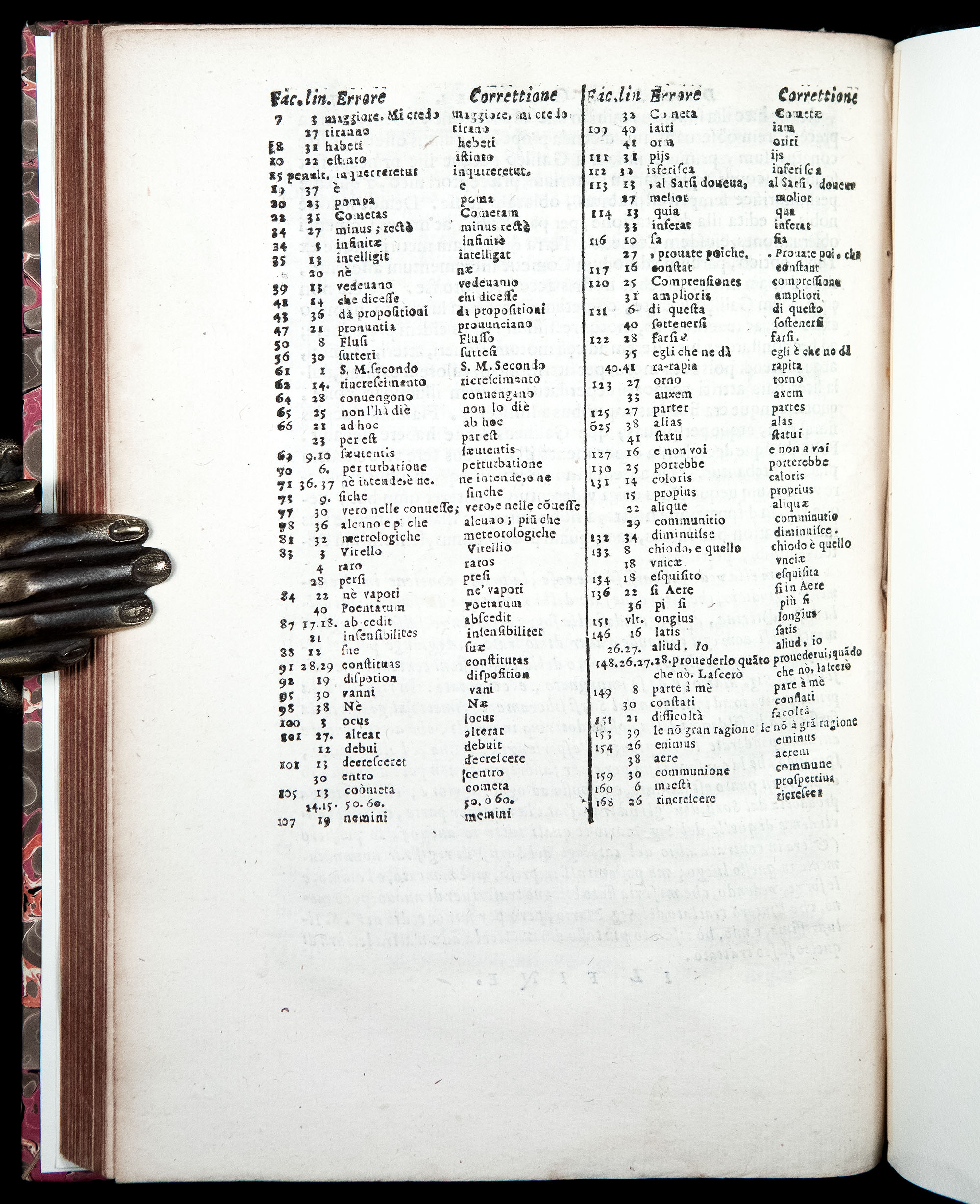

The final (unnumbered) page contains Errata.

Condition:

Near Fine antiquarian condition. Complete. Internally with occasional very light browning, mostly marginal. Else, a remarkably clean, solid, genuine, very wide-margined volume.