[Early Printing - Incunabula - Rare Presses - Cremona]

Francesco Petrarca

De remediis fortunae.

(Edited by Niccolò Lucano.)

$4,500

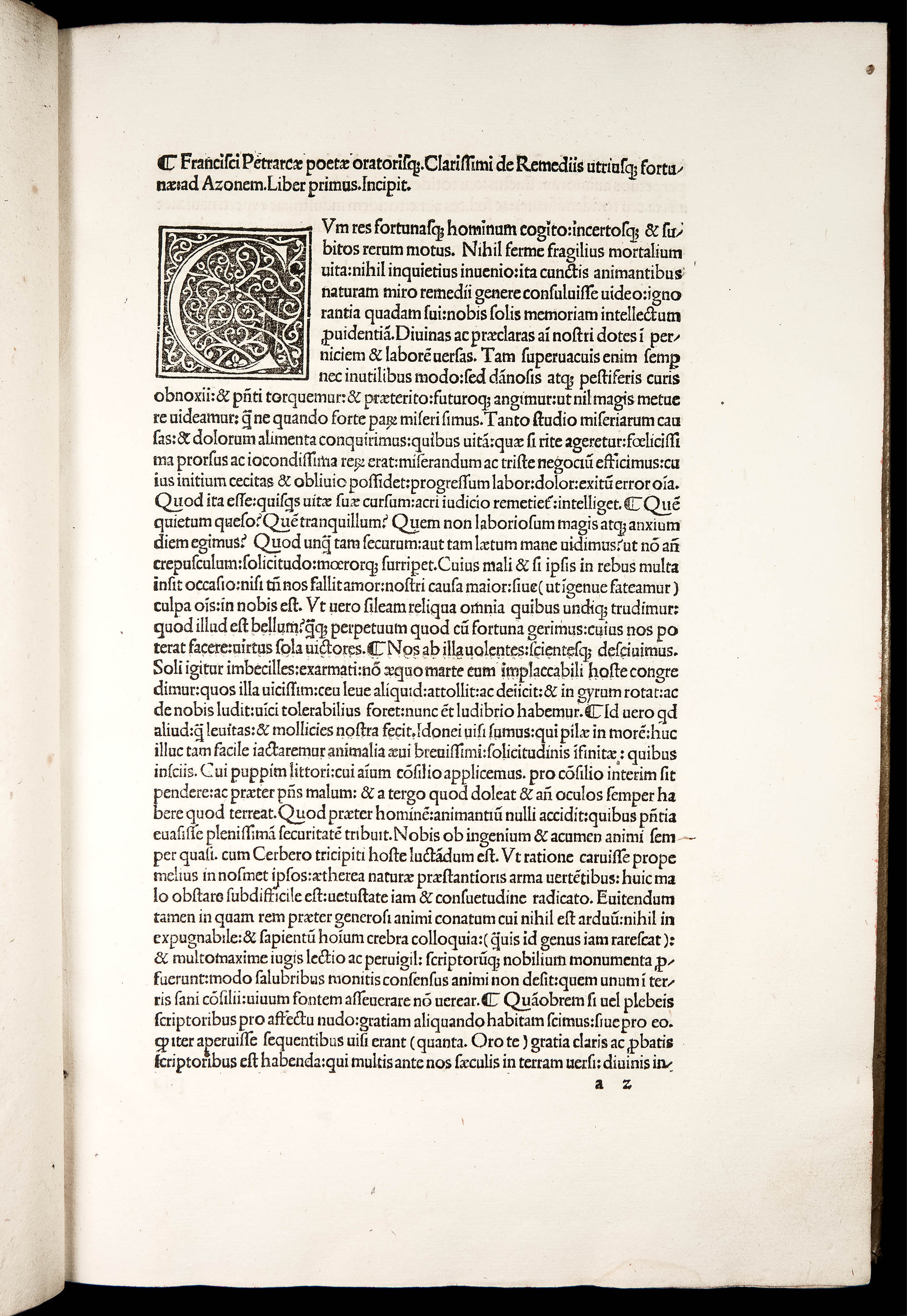

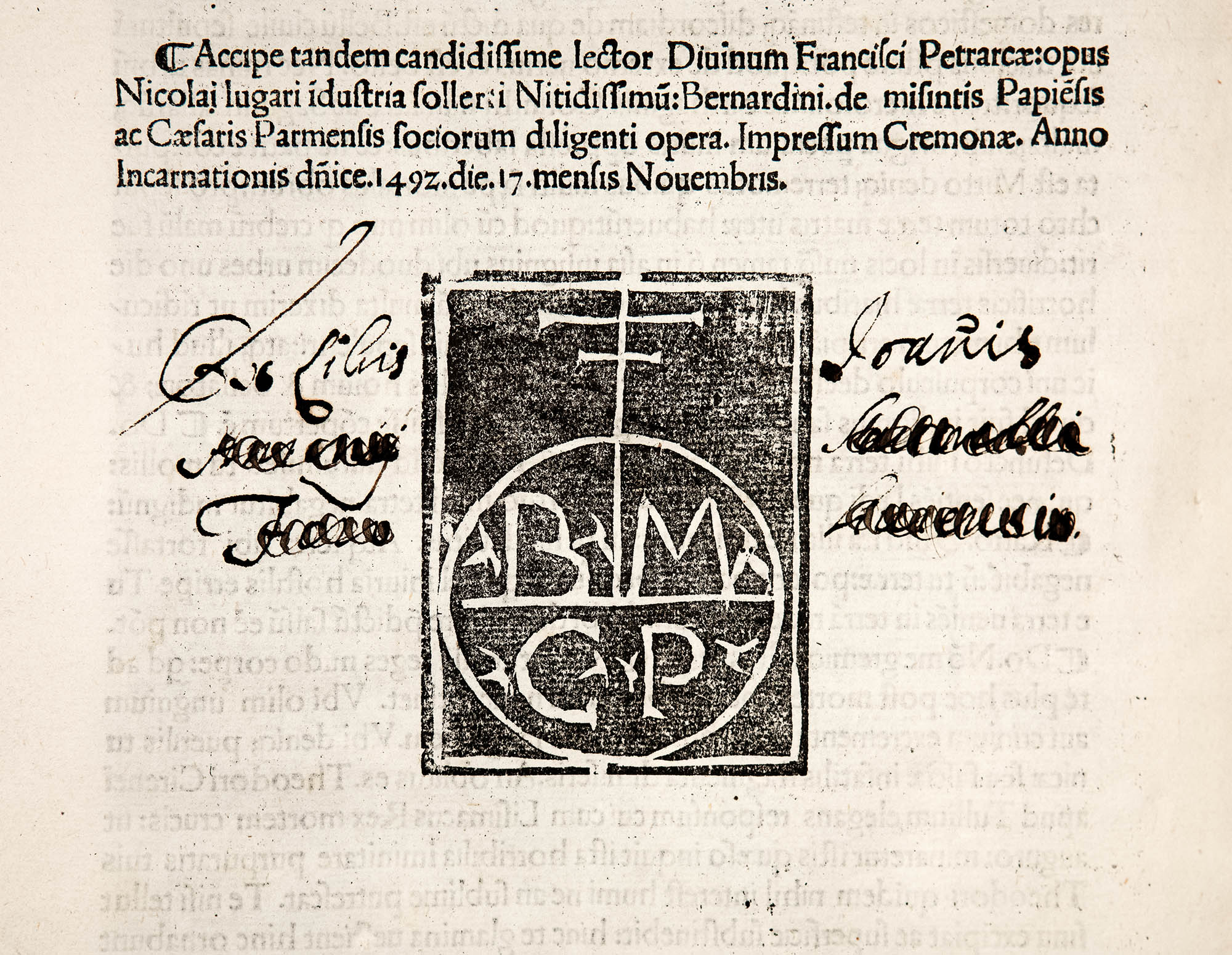

Printed in Cremona by Bernardinus de Misintis and Caesar Parmensis, 17 November 1492.

Third Edition; 1st Lucano edition.

Text in Latin.

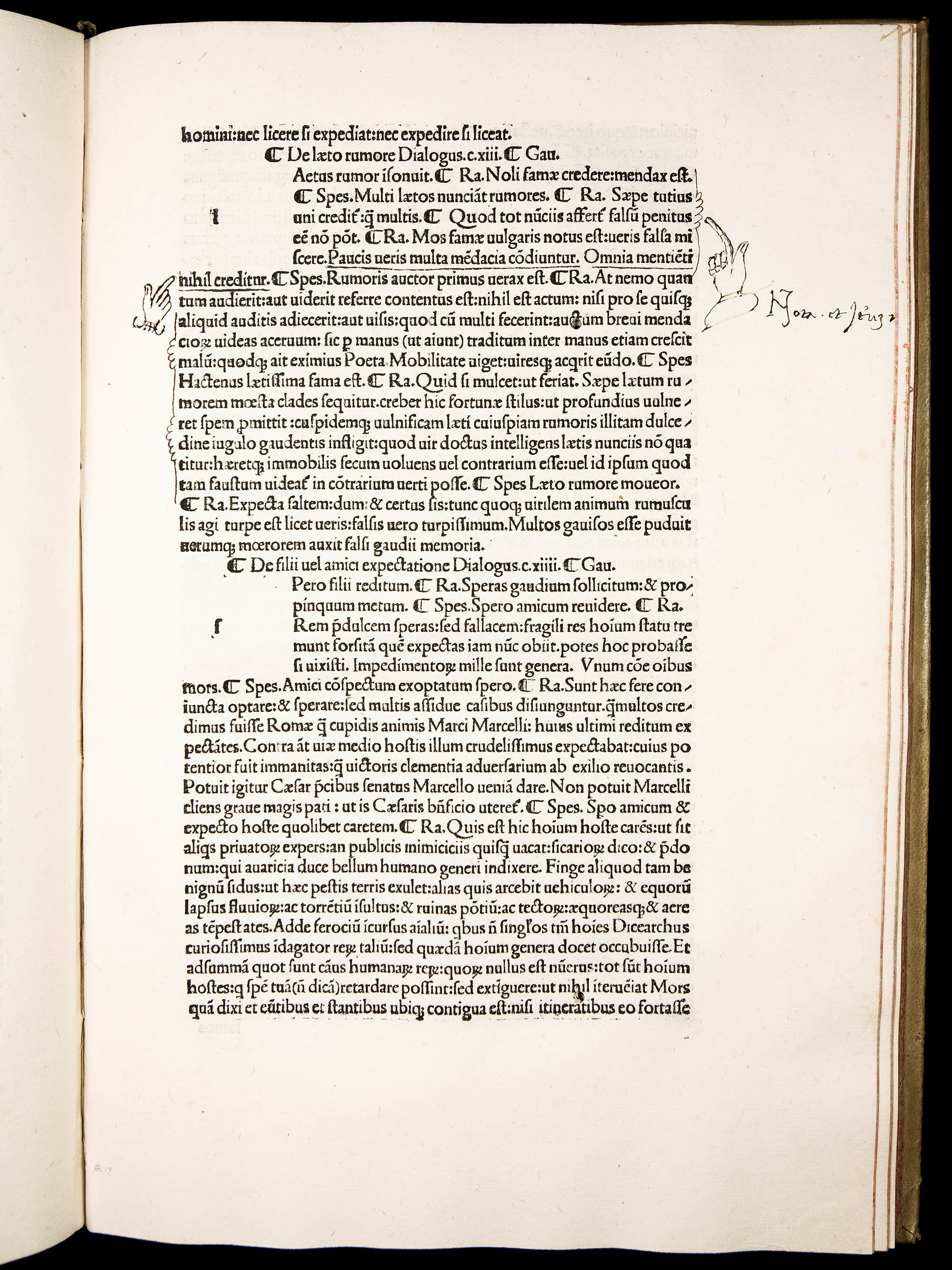

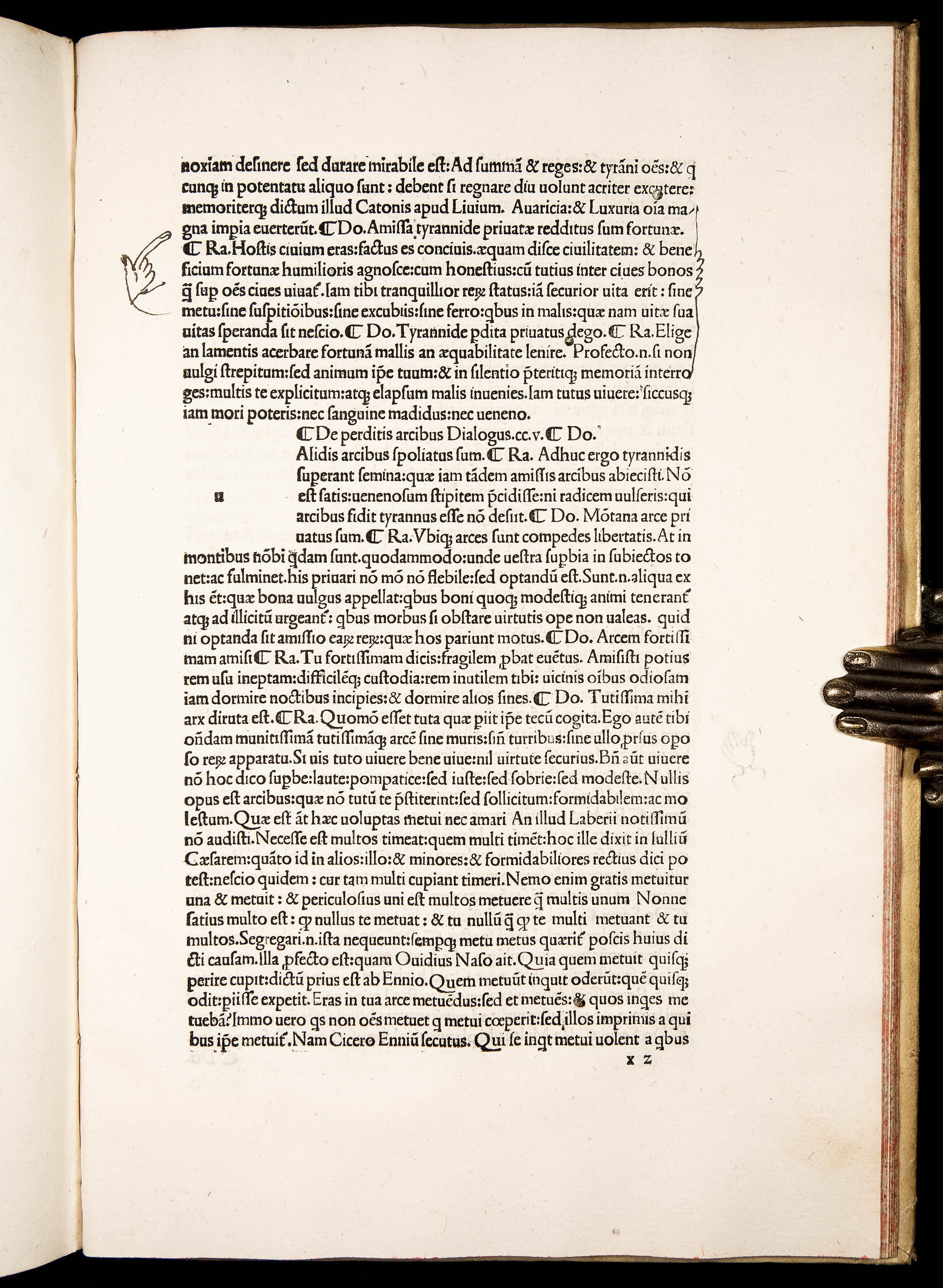

A nice wide-margined copy (with distinguished provenance!) of the scarce 3rd Edition of Petrarch’s celebrated work “On the Remedies for the Good and Bad Fortunes", first printed in 1473. It is a collection of 254 entertaining dialogues offering a bouquet of moral philosophy, set out to show how thought and deed can generate happiness on the one hand, or sorrow and disillusionment on the other. In a recurring theme throughout the dialogues, Petrarch advises humility in prosperity and fortitude in adversity.

"Latin work by Petrarch, begun in 1354 but completed between 1360 and 1366, on how to deal with both good and bad fortune. The first of its two parts contains 122 dialogues between Ratio, Gaudium, and Spes, and deals with how one should behave at times of good fortune; the second contains 131 dialogues between Ratio, Dolor, and Timor, and deals with the behaviour appropriate to adverse fortune. It is a practical manual of moral philosophy, and was widely read until the 17th c." (Oxford Companion to Italian Literature).

The work belongs to the 'consolation' genre of medieval literature, and was influenced by the anonymous De remediis fortuitorum, attributed to Seneca during the Middle Ages, by Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy, as well as by the medieval 'contemptus mundi' literature.

This was the 1st edition edited by Niccolò Lucano (d. 1515), a historian and professor of rhetoric based in Cremona. This 1492 edition is believed to offer a more accurate reading of the text than the preceding two, and, therefore, it served as the textual basis for most of the later editions (up until the modern times), including the text of the De remediis in the 1496 and 1501 editions of the complete works of Petrarch.

Petrarch dedicated De remediis to his friend Azzo da Correggio, a patrician of Parma. Petrarch started writing the book in 1354 with the intention of offering guidance and consolation to his friend Azzo, who himself experienced a painfully changeable fortune during this period, when he twice regained and then again lost control of Parma. However, it was not until 1366 – four years after Azzo's death – that Petrarch’s work was completed.

De remediis utriusque fortunae consists of two parts: first offering a remedy for prosperity, and the other for adversity. Its argument is that what is generally recognized as good fortune is in fact worthless and miserable in all cases, whereas what is generally regarded as a misfortune and calamity is actually the very thing that can prepare one for a good death, and an aid in attaining salvation. The work is written in dialogue, a form preferred for introductory theological books during the Middle Ages. Reason debates with Pleasure and Hope in Part One, and with Sorrow and Fear in Part Two.

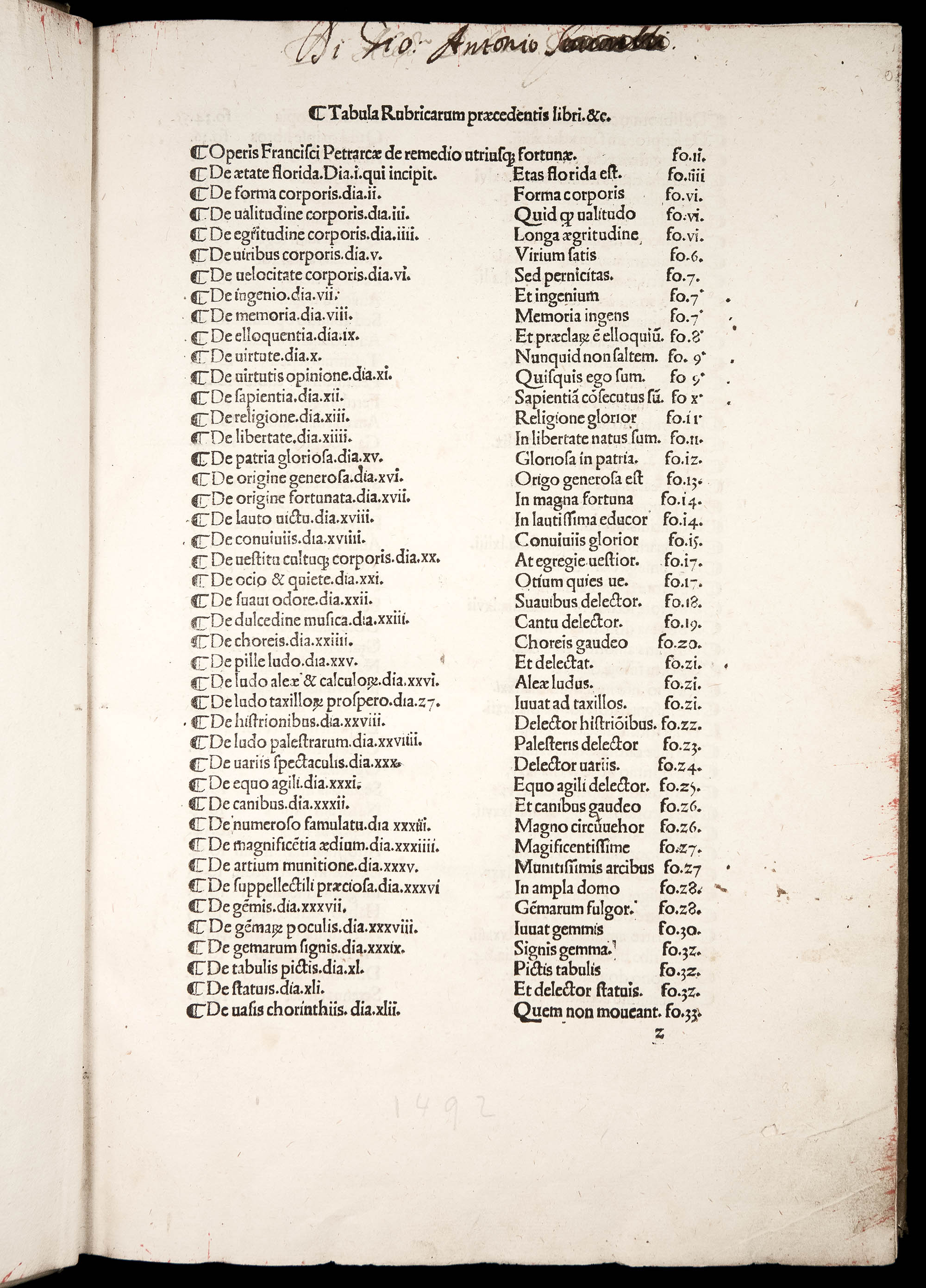

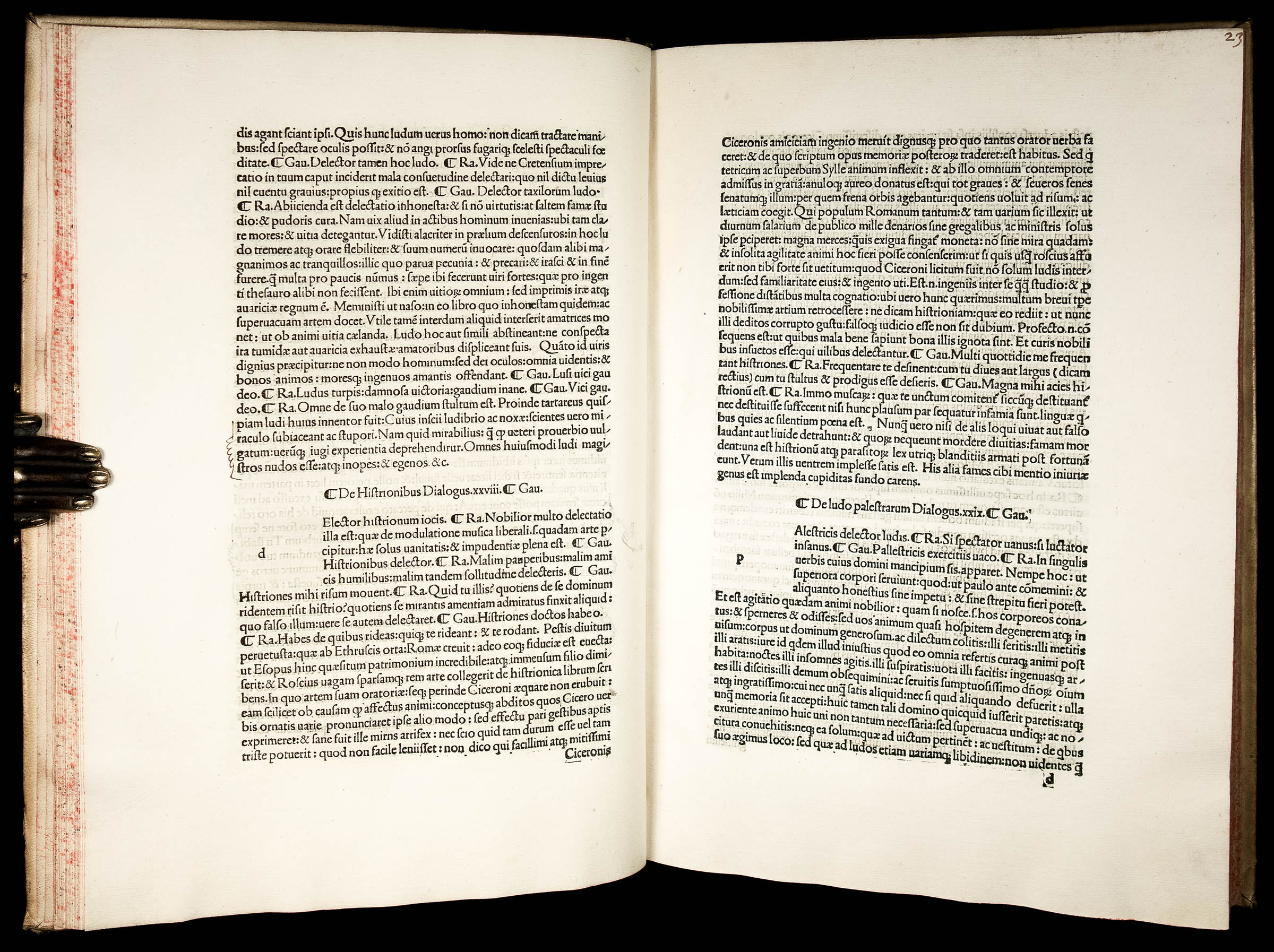

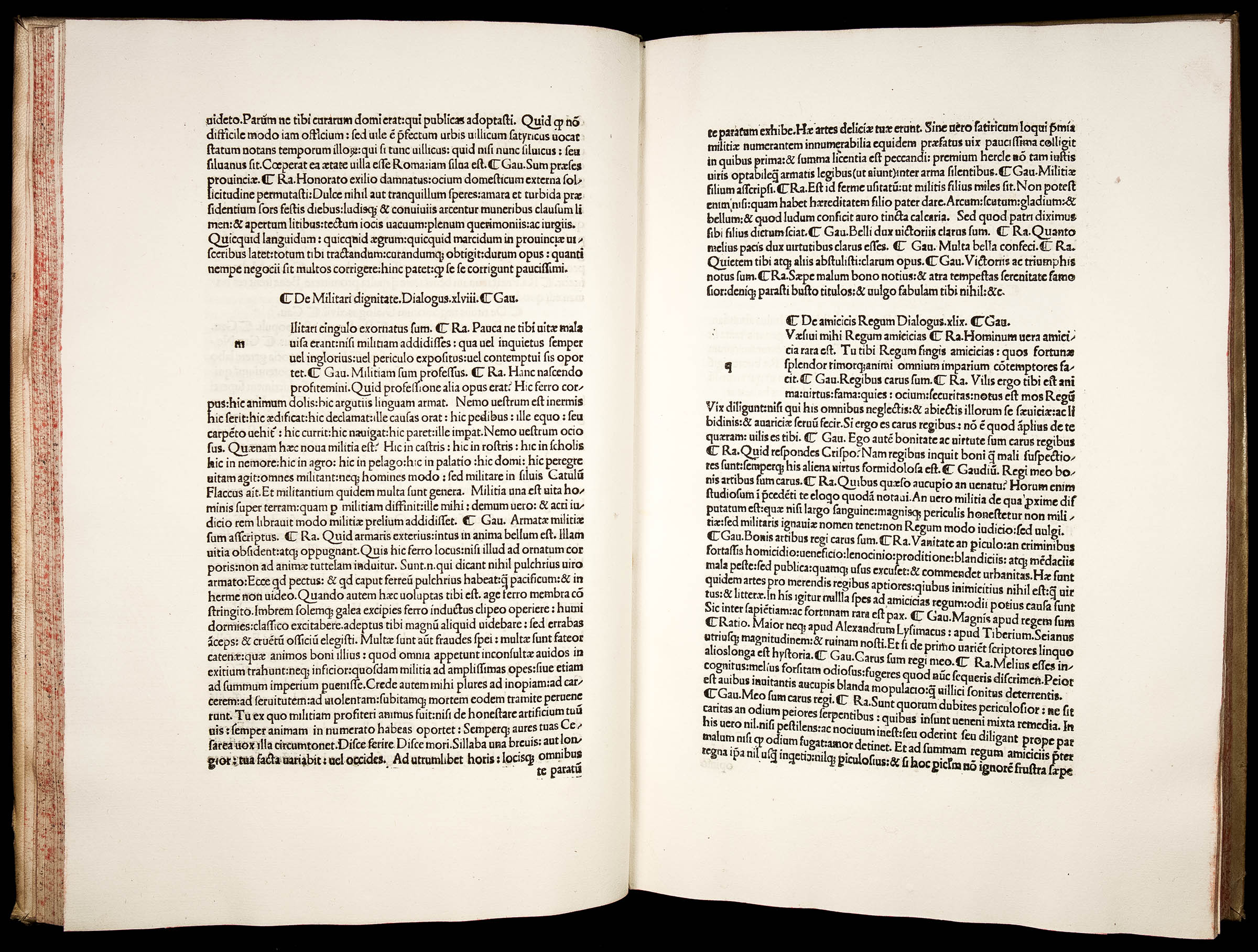

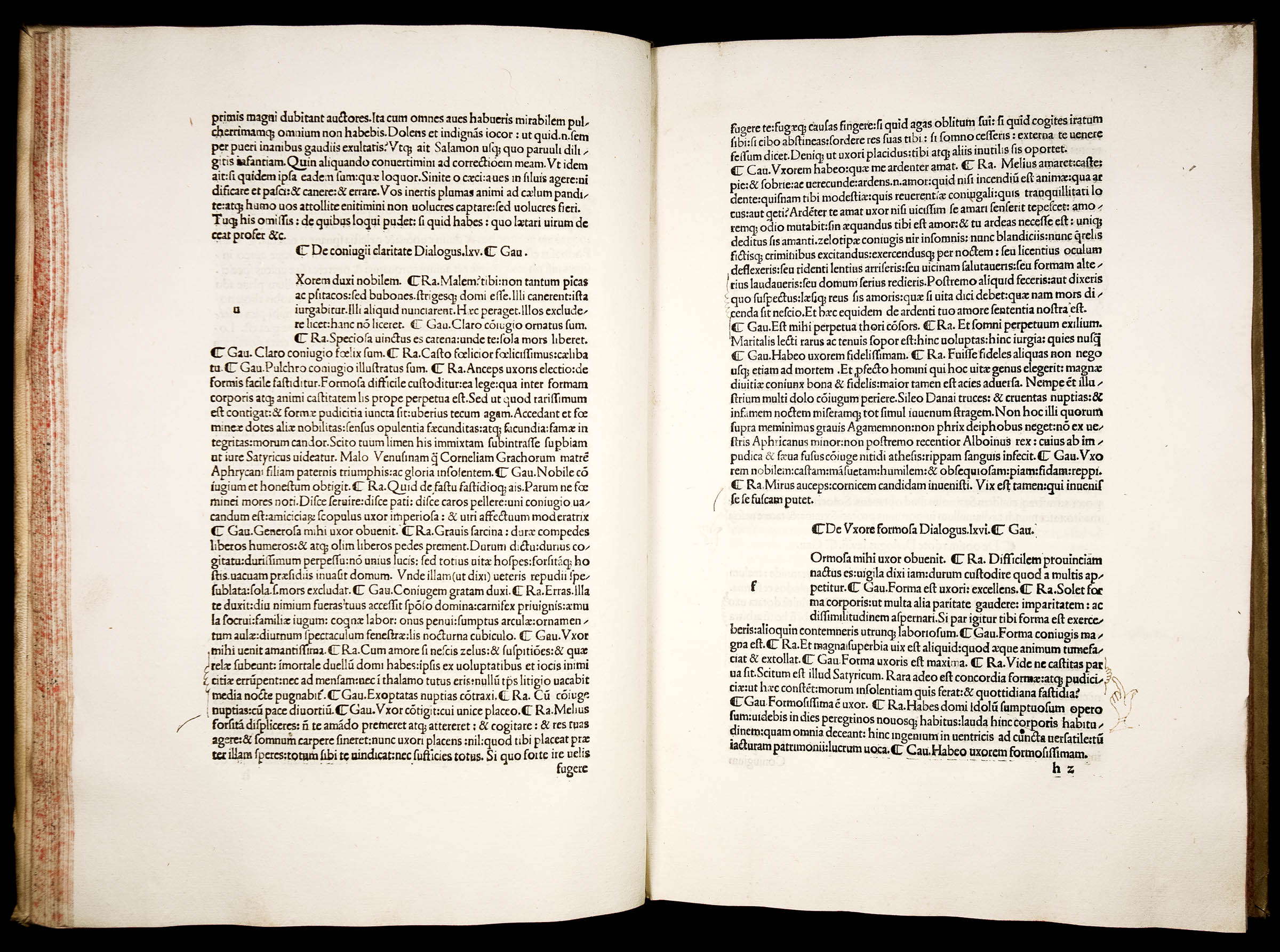

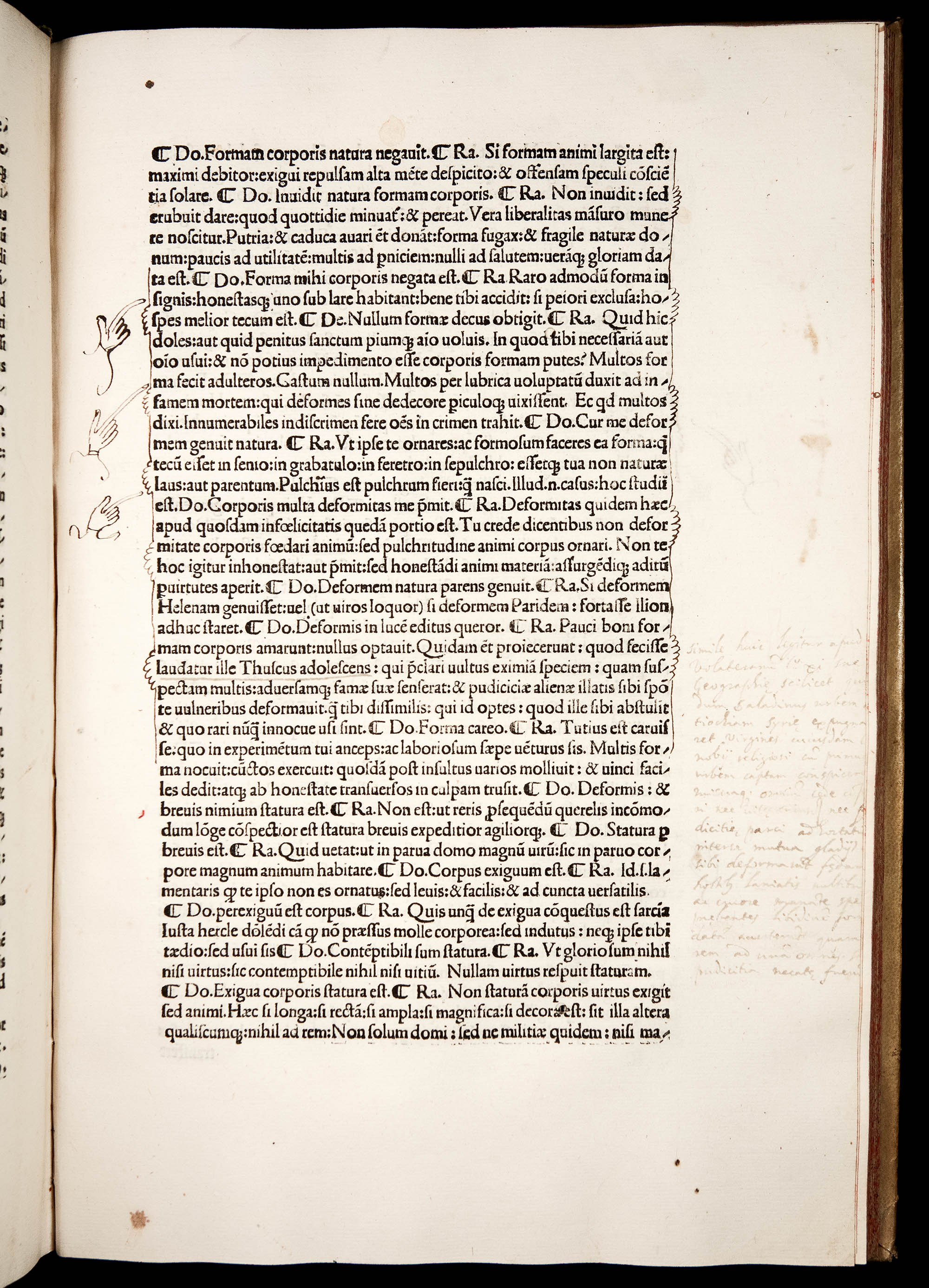

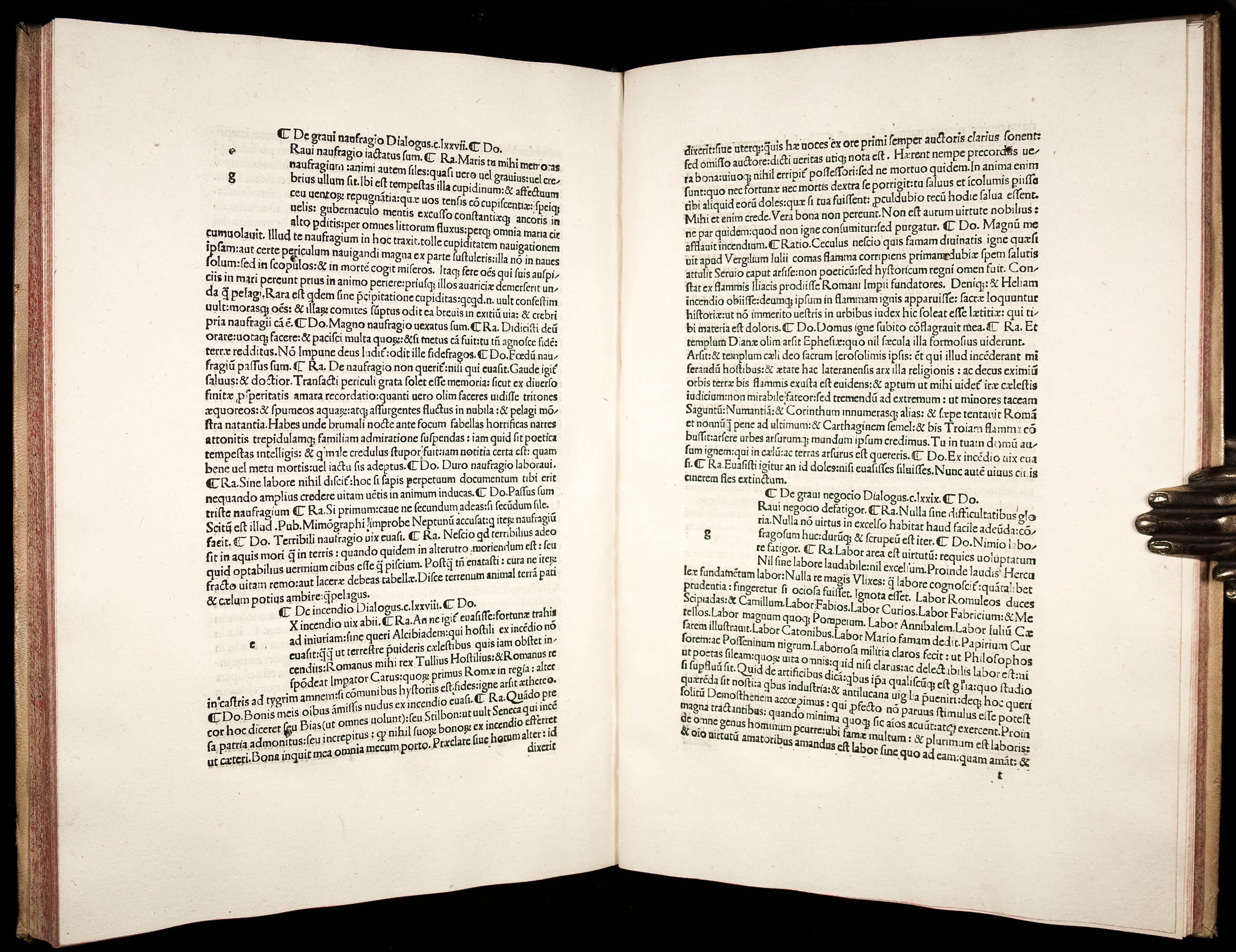

The titles of the dialogues include subjects like: De Ludo Aleae; De Alchimia; De Gravi Naufragio; De Uxore Sterili; De Dolo Malo; De Dulcedine Musica; De Forma Corporis; De Imbecillitate, De Morte Violenta; De Podagra, etc.

Although today De remediis utriusque fortunae is not considered to be representative of Petrarch's work as a humanist, it was his most widely read and best-known work in the 14th and 15th centuries, and was translated into many languages. Many manuscripts are extant, including contemporary English and French translations. The book's Christian morals and numerous quotations from the classics influenced many writers of the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance who frequently made use of it. It was translated into English by the Elizabethan physician Thomas Twyne (1543 - 1613).

This edition is the 2nd of only seven books issued by this press, which was the second earliest printing press in Cremona. “Having completed their last work at Brescia in May, 1492, these partners produced their first short tract at Cremona on the 18th of the following month (Dialogus de contemptu mundi, Hain-Reichling 6123), and followed it up with five or six further editions, the latest of which [was completed on] 18 Aug. 1493. De Misintis was once more printing at Brescia in July 1494, whereas Caesar remained at Cremona to collaborate with Rafainus Ungaronus later in the same year.” (BMC, VII, p.956)

Bibliographic references:

Hain/Copinger 12793; Goff P-409; Proctor 6927; BMC VII p.956; BSB-Ink P-264; GW M31618; Polain 4644; IGI 7578.

Physical description:

Folio, textblock measures 307 mm x 206 mm). Bound in 18th-century full vellum over rigid boards; flat spine with a gilt-lettered label. All edges speckled red.

164 leaves. Collation: π4 [-π1 blank] a-b8 c-z6 A-B6 C8 [-C8 blank].

Complete (bound without the blanks at front and rear π1 and C8).

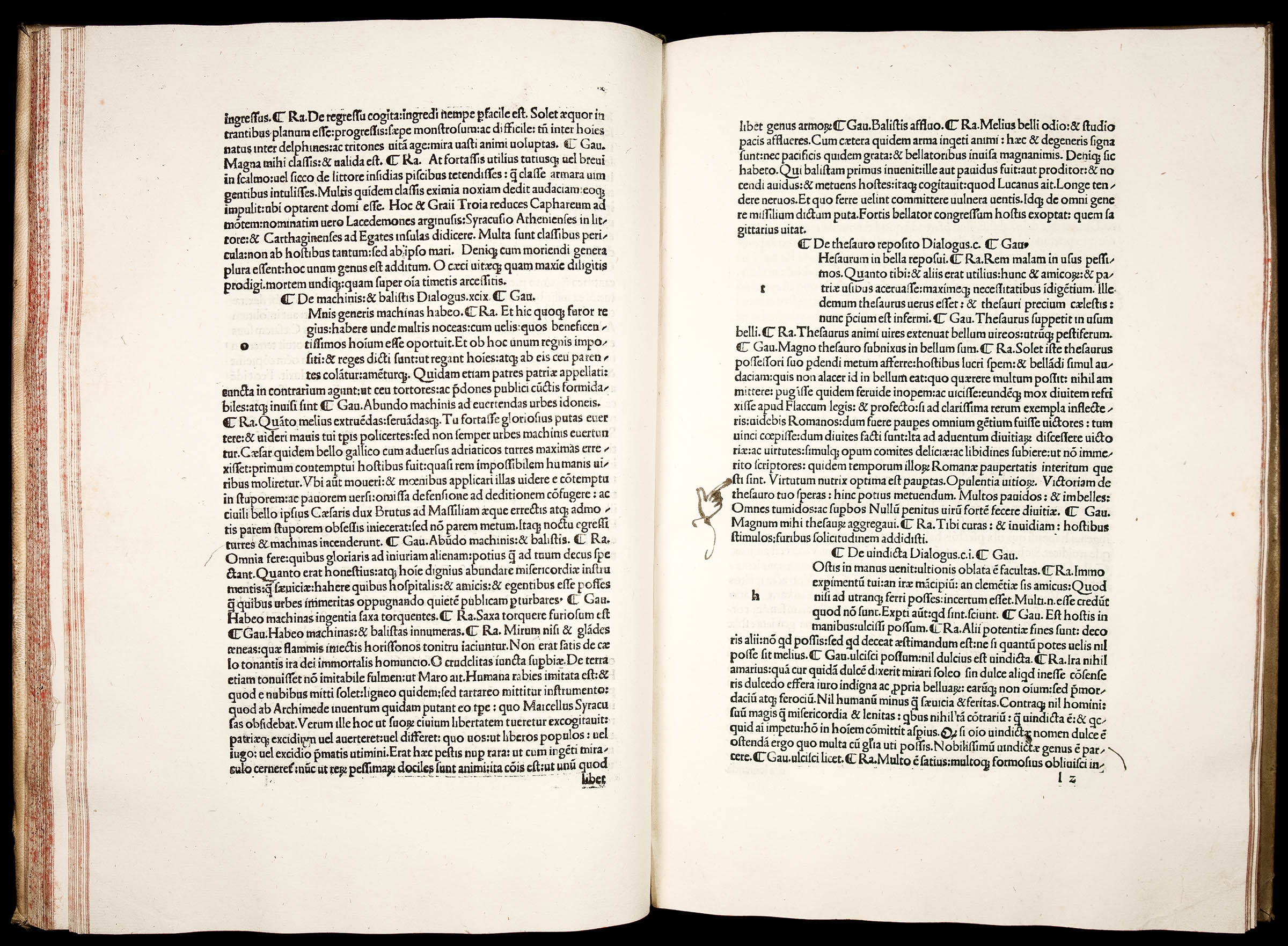

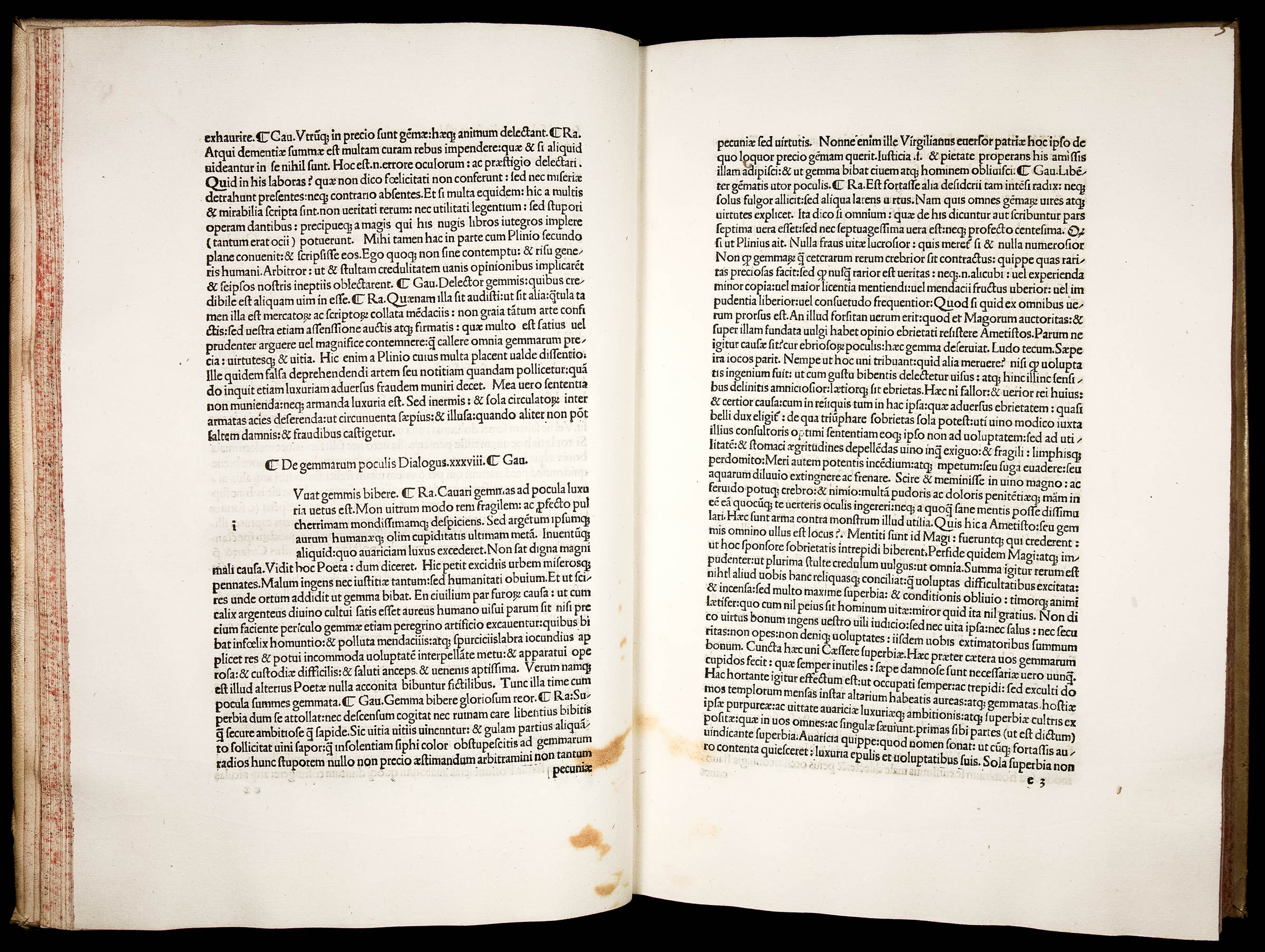

Text printed in single column; 44 lines per page; in roman type (1:102R).

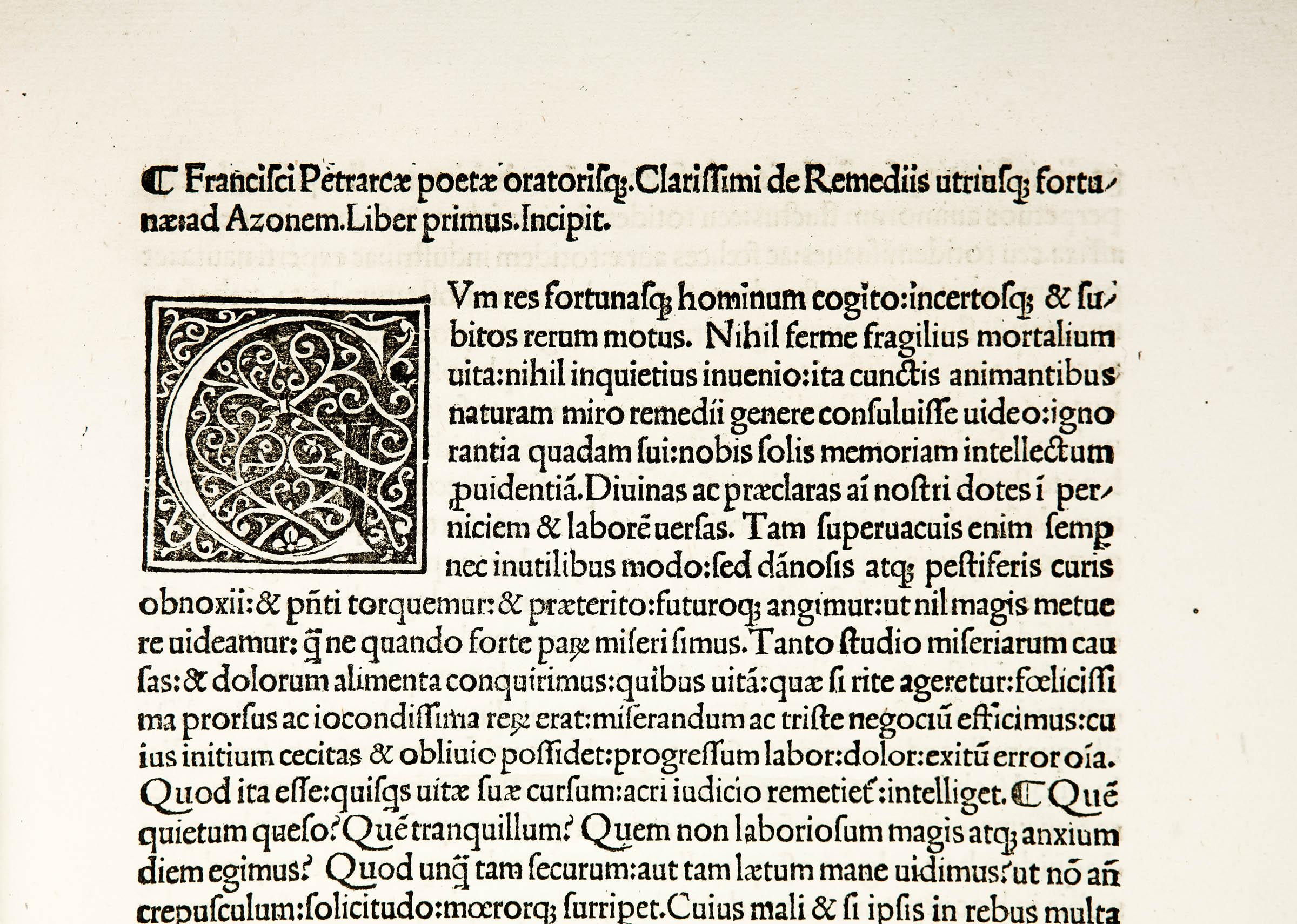

Fine 8-line decorative woodcut initial ‘C’ on leaf a2r, 5-line initial spaces with printed guide-letters (unrubricated); woodcut printer's device on verso of the final leaf (C7v).

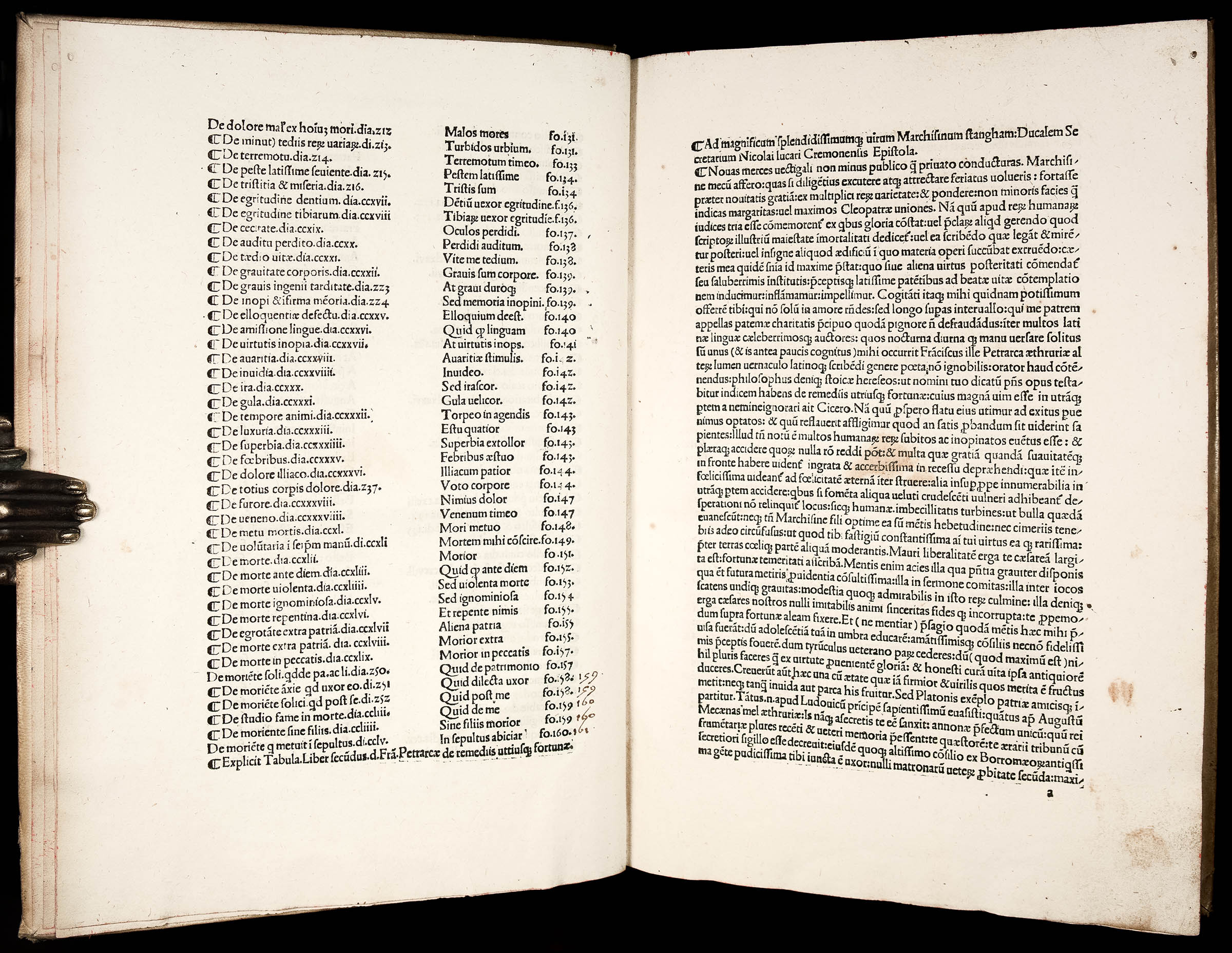

Includes a table of contents (π2r-4v), and a dedicatory epistle by the editor, Niccolò Lucano (a1r,v).

Colophon on C7v.

Provenance:

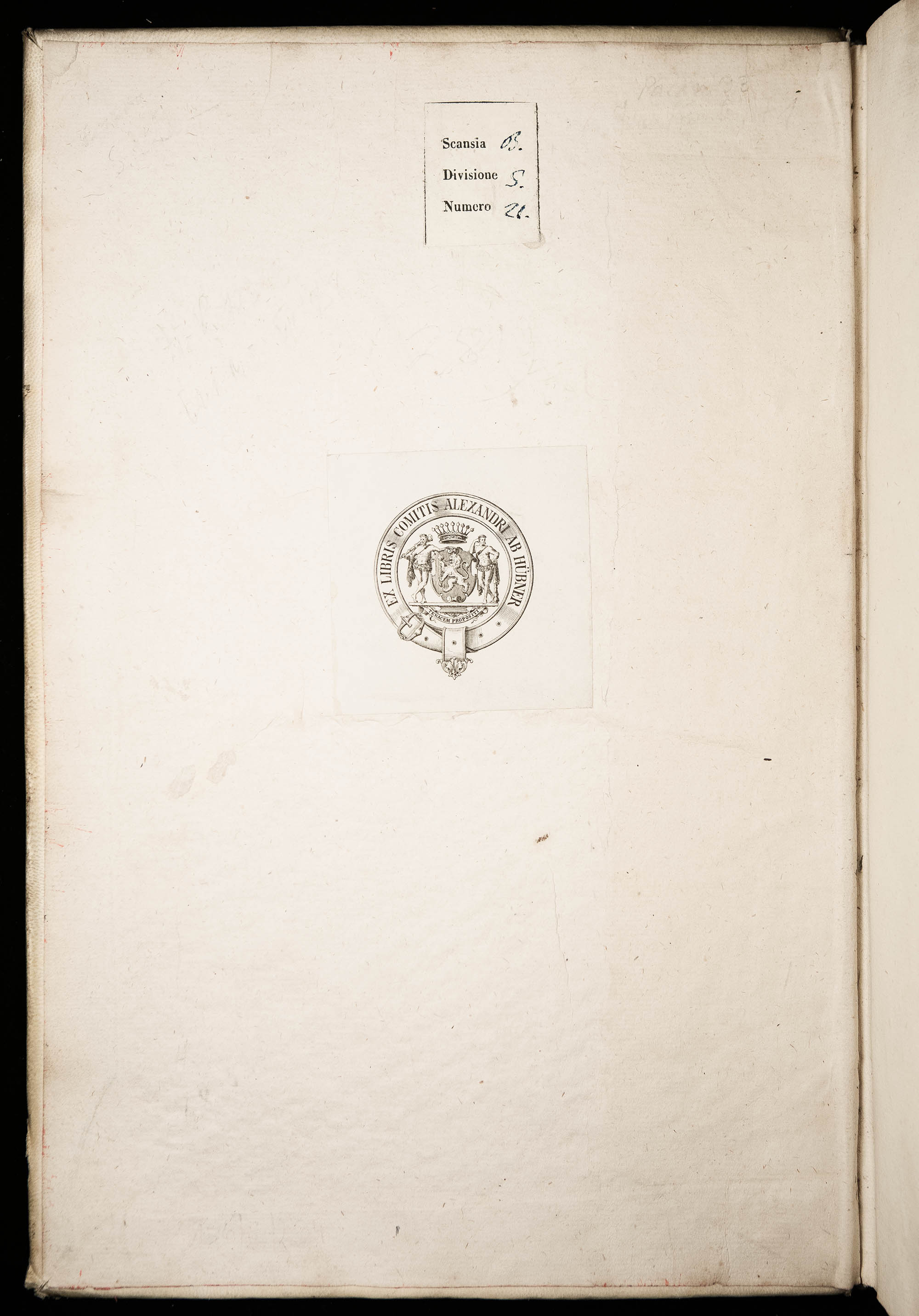

Armorial bookplate (on front pastedown) of Count Alexander Hübner (1811 - 1892) a distinguished Austrian statesman and diplomat who rose from humble circumstances to become one of the leading members of the Austrian foreign service in the 1850s and 1860s. He was educated at Vienna, and began his diplomatic service in the Chancery of State, under Prince Metternich. In 1854 he became baron and in 1857 ambassador to the court of Napoleon. From 1865 to 1867 he served as ambassador at Rome. His 2-volume biographical work on pope Sixtus V was the fruits of his Roman studies. Shortly before his death, Hübner published ‘Ein Jahr meines Lebens: 1848-1849’ (1891), a work that he described as a literal transcription of his daily journal. Given his personal experiences during the legendary "Five Glorious Days" of Milan as well as his insider's view of the counter-revolution in Austria, the book became a standard source on the revolution of 1848 in Italy and Austria. When the Emperor Franz Joseph I raised Hübner to the rank of hereditary count in 1889, the London Daily Telegraphreported the event and referred to him as "the most distinguished Austrian alive." The fame he enjoyed in his later years was primarily the result of a series of travel books that he published in the 1870s and 1880s. Following his retirement from the diplomatic corps in 1871, Hübner became an international celebrity.

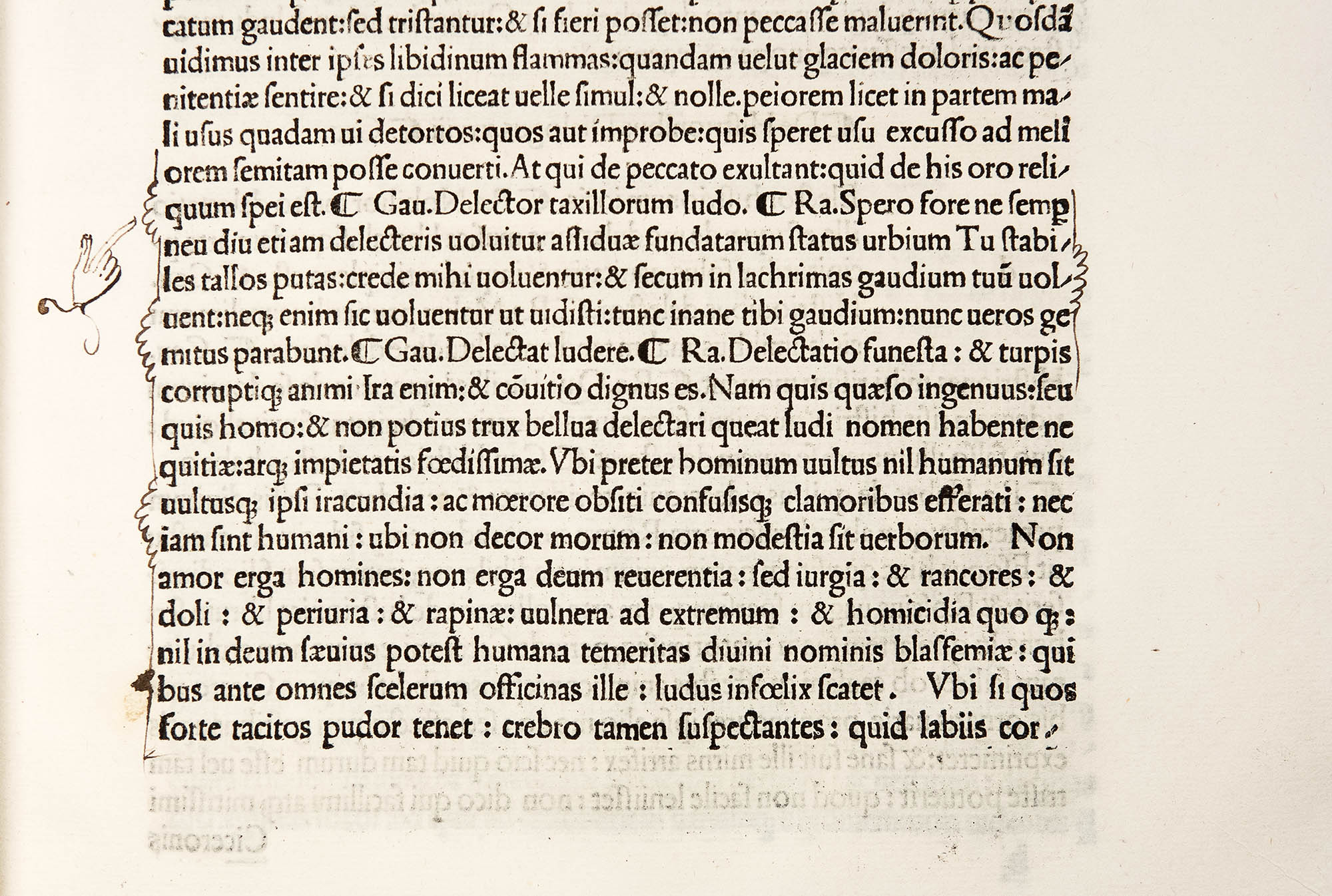

An early Italian ownership inscription (to bottom margin of π2r) in a 16th-century hand “Di Pio Antonio.” Several very pleasing hand-drawn marginal manicules (pointing hands) by the above mentioned or another early owner.

Condition:

Very Good antiquarian condition. Complete. Vellum binding rubbed, light hand-soiling; light wear to corners. Internally with occasional small harmless ink-spots; a few leaves with light stains. Several leaves with well-drawn pen-and-ink marginal manicules and a couple of marginal notes in an early hand. On leaf n1v (dialogue ‘De spe vitae aeternae’) a passage of 5 lines inked out (doubtless by a censor). An early ownership signature to bottom margin of the first page, and another one (crossed out in ink) on the last page under. Towards the end with a few small wormholes, not affecting legibility. Else, a very pleasing, generally clean, genuine, very wide-margined example of this finely printed, scarce edition of one of the classics of early Renaissance literature.