(St. Augustine)

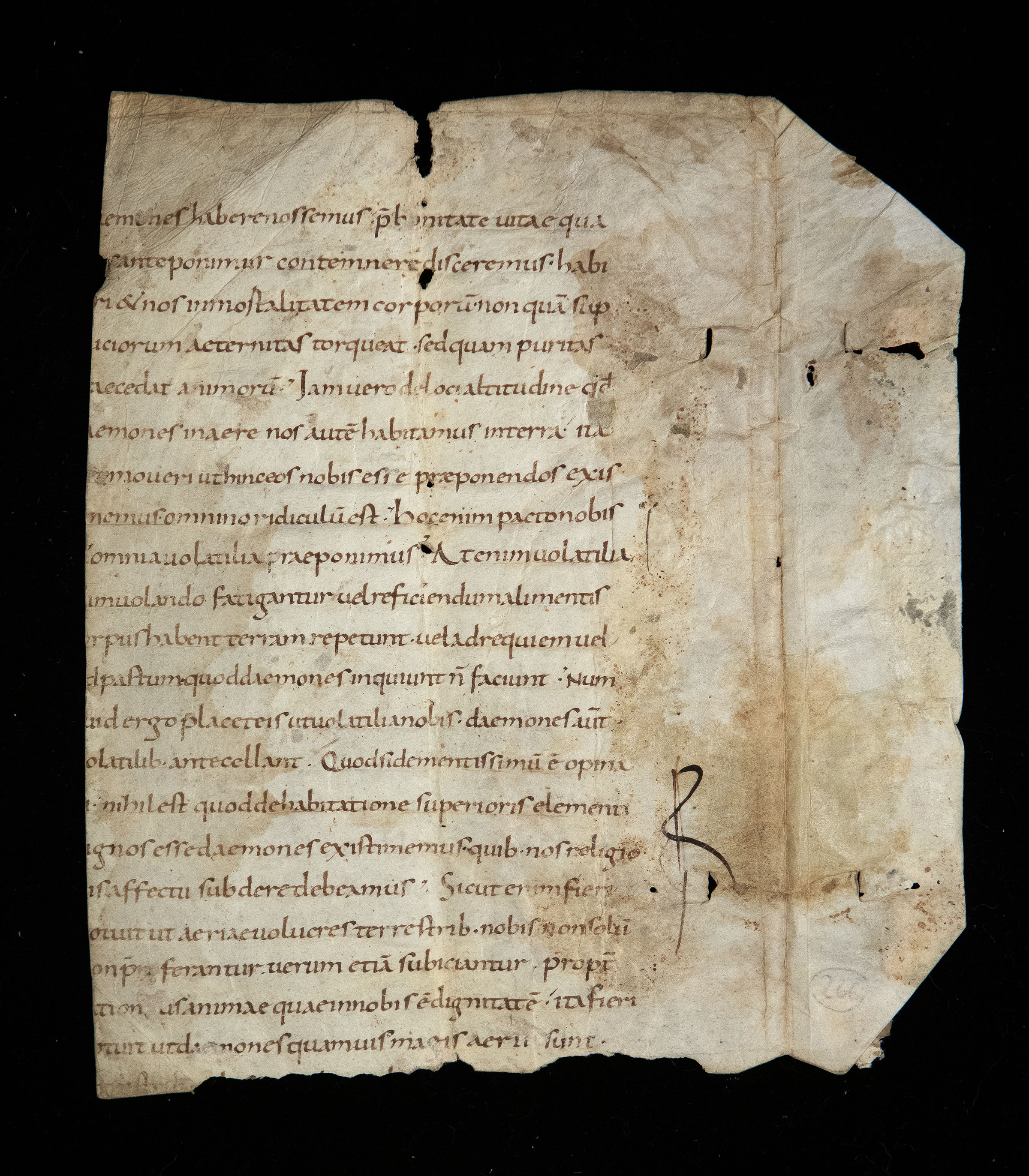

France, likely Tours, 2nd half of 9th century (i.e. 850-900 AD).

Text in Latin.

This is a truly remarkable, substantial fragment of a stunningly early manuscript of St Augustine’s City of God, one of the foundational texts not just of Christian theology, but of the entire Western culture. St. Augustine's De civitate Dei profoundly shaped the Western civilization: from the time of its composition and throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, De civitate Dei remained the most popular and influential of all patristic works. "Few men have influenced human thought as Augustine did Western religion and philosophy.” (DSB)

Pre-1000 AD manuscripts (even in such fragmentary form) of Augustine’s vastly influential work are exceedingly rare.

Moreover, the fragment contains some of the most curious passages of the entire work; the text comes from Book VIII, Chapter 15, where Augustine argues that demons are not better than men because of their subtle aerial bodies or their superior place of abode; and from Chapter 16, presenting the views of Apuleius the Platonist regarding the manners and actions of demons.

The script of this fragment is a superb example of Caroline minuscule at the height of its clarity and aesthetic impact. Evident in all their glory are the classic features of early Carolingian script, such as:

- Exclusive use of the ‘small uncial’ form of ‘a’ with a narrow lobe and with shaft - which gradually became more upright in later Carolingian hands - here distinctly sloping to the right;

- First two minims of ‘m’ have no ‘feet’ and are noticeably curling leftward;

- Exclusive use of a ‘long s’ in all positions, etc.

The script also exhibits some archaic features evoking earlier, pre-Carolingian regional scripts, still observed in the earliest Carolingian hands (late 8th - early 9th century), such as:

- An uncommon tall and awkwardly pointy ‘rt’ ligature (in ‘inmortalitatem’, line 3 on recto), similar to that used by the scribe of the Vatican Livy (Reg. lat. 762) produced at Tours between 775 and 825.

- Gaps between words are very small, often nonexistent, like in the Scriptio continua style of manuscripts of the classical antiquity (e.g. the ca. 400 AD Vergilius Vaticanus). This feature was often seen in manuscripts of the early 9th century (e.g. the Vatican Livy, Reg. lat. 762), but gradually vanished; by the 10th century, the spaces became much more pronounced and standardized.

- Occasional use of the ‘g’ with semi-open loops resembling ‘3’ (in ‘ergo’, line 13 on recto).

That being said, the script clearly possesses some transitional features characteristic of the evolving Carolingian book-hand from the later 9th and early 10th century: the lettering becomes slightly thinner, the clubbing of the main strokes less pronounced, and tops of some ascenders start to display rudimentary serifs.

The text on recto comprises the following passage (very clearly legible, with only minor losses of a few letters per line due to cropping on the left side):

“…daemones habere nossemus, prae bonitate vitae, qua illis anteponimur, contemnere disceremus, habituri et nos inmortalitatem corporum, non quam suppliciorum aeternitas torqueat, sed quam puritas praecedat animorum. Iam vero de loci altitudine, quod daemones in aere, nos autem habitamus in terra, ita permoveri, ut hinc eos nobis esse praeponendos existimemus, omnino ridiculum est. Hoc enim pacto nobis et omnia volatilia praeponimus. At enim volatilia cum volando fatigantur vel reficiendum alimentis corpus habent, terram repetunt vel ad requiem vel ad pastum, quod daemones, inquiunt, non faciunt. Numquid ergo placet eis, ut volatilia nobis, daemones autem etiam volatilibus antecellant? Quod si dementissimum est opinari, nihil est quod de habitatione superioris elementi dignos esse daemones existimemus, quibus nos religionis affectu subdere debeamus. Sicut enim fieri potuit, ut aeriae volucres terrestribus nobis non solum non praeferantur, verum etiam subiciantur propter rationalis animae, quae in nobis est, dignitatem: ita fieri potuit, ut daemones, quamvis magis aerii sunt” (Lib. VIII, Cap. 15),

...which translates,

“…we should learn to despise the bodily excellence of the demons compared with goodness of life, in respect of which we are better than they, knowing that we too shall have immortality of body,- not an immortality tortured by eternal punishment, but that which is consequent on purity of soul.But now, as regards loftiness of place, it is altogether ridiculous to be so influenced by the fact that the demons inhabit the air, and we the earth, as to think that on that account they are to be put before us; for in this way we put all the birds before ourselves. But the birds, when they are weary with flying, or require to repair their bodies with food, come back to the earth to rest or to feed, which the demons, they say, do not. Are they, therefore, inclined to say that the birds are superior to us, and the demons superior to the birds? But if it be madness to think so, there is no reason why we should think that, on account of their inhabiting a loftier element, the demons have a claim to our religious submission. But as it is really the case that the birds of the air are not only not put before us who dwell on the earth; but are even subjected to us on account of the dignity of the rational soul which is in us, so also it is the case that the demons, though they are aerial…”

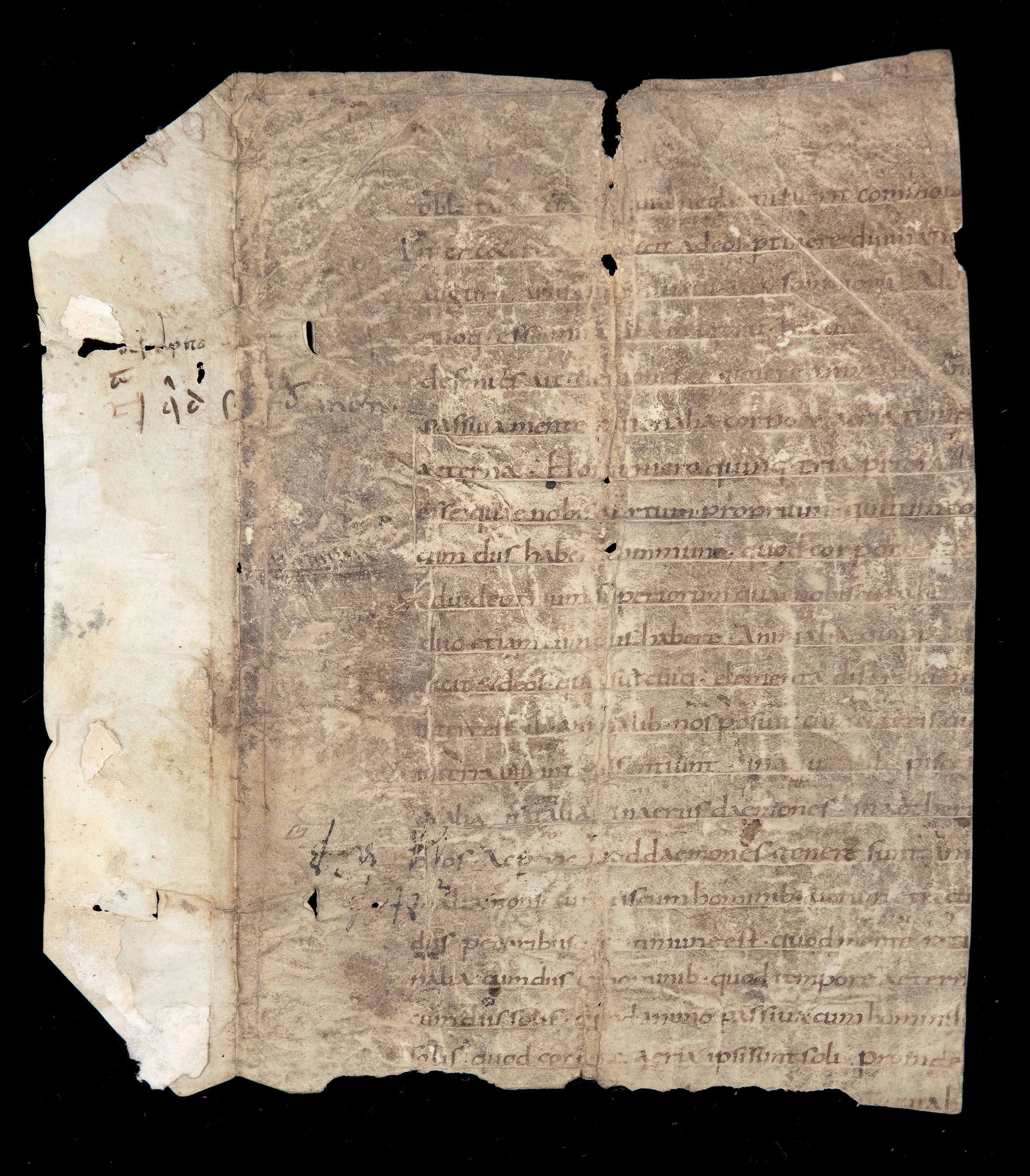

The text on verso comprises the following passage (although with many words obscured through extensive darkening and rubbing):

“… oblectari et in eis si quid neglectum fuerit commoveri. Inter cetera etiam dicit ad eos pertinere divinationes augurum, aruspicum, uatum atque somniorum; ab his quoque esse miracula magorum. Breviter autem eos definiens ait daemones esse genere animalia, animo horum vero quinque tria priora illis esse quae nobis, quartum proprium, quintum eos cum diis habere commune. Sed video trium superiorum, quae nobiscum habent, duo etiam cum diis habere. Animalia quippe esse dicit et deos, suaque cuique elementa distribuens in terrestribus animalibus nos posuit cum ceteris, quae in terra vivunt et sentiunt, in aquatilibus pisces et alia natatilia, in aeriis daemones, in aetheriis deos. Ac per hoc quod daemones genere sunt animalia, non solum eis cum hominibus, verum etiam cum diis pecoribusque commune est; quod mente rationalia, cum diis et hominibus; quod tempore aeterna, cum diis solis; quod animo passiva, cum hominibus solis; quod corpore aeria, ipsi sunt soli.”

...which translates,

“… and [demons] are annoyed if any of them be neglected. Among other things, he also says that on them depend the divinations of augurs, soothsayers, and prophets, and the revelations of dreams, and that from them also are the miracles of the magicians. But, when giving a brief definition of them, [Apuleius] says, that demons are of an animal nature, passive in soul, rational in mind, aerial in body, eternal in time. Of which five things, the three first are common to them and us, the fourth peculiar to themselves, and the fifth common to therewith the gods. But I see that they have in common with the gods two of the first things, which they have in common with us. For he says that the gods also are animals; and when he is assigning to every order of beings its own element, he places us among the other terrestrial animals which live and feel upon the earth. Wherefore, if the demons are animals as to genus, this is common to them, not only with men, but also with the gods and with beasts; if they are rational as to their mind, this is common to them with the gods and with men; if they are eternal in time, this is common to them with the gods only; if they are passive as to their soul, this is common to them with men only; if they are aerial in body, in this they are alone.”

Augustine of Hippo, or Saint Augustine (354 - 430), is one of the most important figures in the development of Western Christianity. In Roman Catholicism and the Anglican Communion, he is a saint and pre-eminent Doctor of the Church, and the patron of the Augustinian religious order. Many Protestants, especially Calvinists, consider him to be one of the theological forerunners of the Reformation view on salvation and grace. In Orthodox Churches he is considered blessed, or even a saint by some, while others are of the opinion that he is a heretic. Born in Africa as the eldest son of Saint Monica, he was educated in Africa and baptized in Milan.

“Aurelius Augustinus, Bishop of Hippo in North Africa, was one of the four great Fathers of the Latin Church. In his Confessiones he described the influence of God's action on the individual. In The City of God theology is shown in relation to the history of mankind and God's action in the world is explained. The first five books deal with the polytheism of Rome, the second five with Greek philosophy, particularly Platonism and Neo-Platonism, and the last twelve books with the history of time and eternity as set out in the Bible. History is conceived as the struggle between two communities - the Civitas coelestis of those inspired by the love of God, leading to contempt of self, and the Civitas terrena, or diaboli, of those living according to man, which may lead to contempt of God" (Printing and the Mind of Man).

“St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) was one of the most prolific geniuses that humanity has ever known, and is admired not only for the number of his works, but also for the variety of subjects, which traverse the whole realm of thought. The form in which he casts his work exercises a very powerful attraction on the reader. In The City of God […] Augustine answers the pagans, who attributed the fall of Rome (410) to the abolition of pagan worship. Considering this problem of Divine Providence with regard to the Roman Empire, he widens the horizon still more and in a burst of genius he creates the philosophy of history, embracing as he does with a glance the destinies of the world grouped around the Christian religion, the only one which goes back to the beginning and leads humanity to its final term. The City of God is considered as the most important work of the great bishop. The other works chiefly interest theologians; but [The City of God], like the Confessions, belongs to general literature and appeals to every soul. The Confessions are theology which has been lived in the soul, and the history of God's action on individuals, while The City of God is theology framed in the history of humanity, and explaining the action of God in the world." (Catholic Encyclopedia).

The City of God is St. Augustine's most important theological work. Augustine wrote the treatise to explain Christianity's relationship with competing religions and philosophies. It was written soon after Rome was sacked by the Visigoths in 410. Augustine's work, which lays out the fundamental contrast between Christianity and the secular world, stands as the supreme exposition of a Christian philosophy of history. In the middle ages "the writings of Augustine contained perhaps the most substantial body of philosophical ideas then available in Latin." (Kristeller, Augustine and the Early Renaissance, Studies in Renaissance Thought and Letters, vol. I, p.357).

Among various philosophical and theological topics, Augustine’s work includes an interesting and influential discourse on demonology:

“Augustine addressed demonological issues throughout the corpus of his writings, but his most explicit treatment occurs in the City of God. In this work Augustine […] set out to confirm the superiority and enduring value of the Christian message. According to him, earthly cities may vanish, but God's kingdom will endure. Within this context Augustine established a platform to discuss the origin and nature of the demonic.

“In the City of God Augustine considers Greek philosophy as superior to all other types, although not without its faults, and in this conversation he commences his discussion of demonology. Specifically, he analyzes the views of Apuleius, a prominent Neo-Platonist, concerning the nature of demons. Apuleius asserted that the world is composed of three rational creatures – gods, humans, and demons. Both good and evil demons exist and they reside in the air as intermediary creatures between the gods and humanity. Apuleius also described demons as having “an animal nature, passive in soul, rational in mind, aerial in body, eternal in time. […]

“On a few significant points Augustine's understanding of demons diverged from the Neo-Platonic views set forth by Apuleius. He denied that demons can be good or evil; that they are intermediaries between the gods and creation; and that they are greater than humans. Concerning the first of these points, Augustine grounded the origin of demons within the angelic rebellion, thus he upheld that all of them are evil. […] On one point, however, Augustine agrees with Apuleius. Both maintain that demons have aerial bodies. […] (David L Bradnick, Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic, p.39-43)

A substantial fragment (extracted from a 15th-century binding where it was used as a liner) measuring about 17 cm by 15.5 cm, of a single leaf of a manuscript on vellum. Apparently comprising the top half of a folio-sized leaf, and containing 21 nearly complete lines of text on each side (with only a couple of letters per line missing due to cropping of the inner margin).

Written in dark-brown ink in an elegant, rather rounded Carolingian bookhand, with minimal spacing between words.

Lines of dry-point ruling revealed on verso (due to wear and soiling).

Some general wear, soiling and tears due to its former use in a binding. Bottom edge slightly chipped and uneven. A few small holes or short harmless tears, but not affecting text. Verso with extensive darkening (due to dust-soiling?) obscuring or impeding legibility of several words. Recto is generally clean, bright with all text eminently legible, with only some minor (and mostly marginal) soiling and very light water-staining. A few minor marginal ink-markings in later hands.